|

By David L.

Lewis

Wartime

requires homefront heroes, as well as battlefield heroes. The American

War for Independence produced Robert Morris, the "financier of the

Revolution," the man who supplied Washington’s army. The Civil

War produced Jay Cooke, the super-bond salesman who helped finance the

Union cause. World War I homefront heroes included Charles Schwab,

Bernard Baruch, Thomas Edison and Henry Ford.

The December

1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor prompted an all-out effort to boost

industrial production as quickly as possible. General Motors, Curtiss-Wright,

Ford, Kaiser, DuPont and Chrysler, among others, quickly established

themselves as leading defense contractors. Each company’s efforts were

publicized to one degree or another, but none received more recognition

than Henry Ford, who became one of the nation’s prime symbols of

wartime production heroics.

Henry Ford

not only personified his company—he was the company for four

decades prior to World War II. During the war the company finally

superseded the man in importance. Even so, the wartime focus remained on

the man, not the company. Henry Ford

not only personified his company—he was the company for four

decades prior to World War II. During the war the company finally

superseded the man in importance. Even so, the wartime focus remained on

the man, not the company.

Until August

1942 virtually all of the publicity about Henry Ford and his company was

extremely favorable. The press glowed with accounts of Ford’s World

War I record, his transformation from a pre-World War II pacifist to a

war producer, and his real and alleged foresight in gearing his company

for military production before America’s entry into the war.

But if the

press applauded Ford’s earlier stance on military production, it

almost ran out of superlatives in discussing his contribution to the

World War II defense effort. From early 1942, despite all else that Ford

was doing, nearly all of this discussion centered around Ford’s Willow

Run bomber plant, which in the minds of many Americans symbolized both

the Ford war effort and America’s intent to fill the skies with heavy

bombers.

Several

factors contributed to the dramatization of Willow Run. At a time when

aircraft industrial leaders were highly skeptical of plans to

mass-produce airplanes, the plant embodied a daring attempt—the first—to

produce aircraft on a full-blown assembly-line system. Moreover, Willow

Run was operated by America’s premier manufacturer—the man popularly

credited with having invented mass production and universally regarded

as its foremost exponent. Many people took it for granted that Ford’s

newest plant, like his renowned Highland Park and River Rouge factories,

would blaze new methods of manufacturing and set new production records.

Willow Run

also impressed everyone by its size. The main building was

3,200-by-1,180 feet, with more than 2.5 million square feet of floor

space—more floor area than the prewar airplane manufacturing factories

of Consolidated Aircraft Corporation, Douglas Aircraft Company and

Boeing Aircraft Company combined. "There seems to be no end to

anything," enthused one journalist. "Like infinity, it

stretches everywhere into the distance of man’s vision."

Completed in

1941, the plant was the largest factory in the world under a single

roof, and remained so until the 1943 completion of Chrysler’s mammoth,

but less publicized, Chicago aircraft engine plant. (The Chrysler plant

was less publicized for two reasons. It produced an engine, rather than

a plane. Also, the plant, along with its parent Chrysler Corporation,

was managed by unknowns; Walter P. Chrysler died in 1940.)

Apart from

its size, Willow Run was assigned one of the war’s glamour products—the

four-engine, long-range B-24 bomber, one of the biggest, fastest and

most destructive aircraft in the world. Amid the gloom of 1942, the

United States looked with hope to the B-24 (labeled the Liberator by the

British) and its companion bomber, the B-17. "These planes,"

declared Fortune magazine in April 1942, "represent our

supreme bid to regain the initiative. They may save our honor, our hopes—and

our necks."

Willow Run,

located near Ypsilanti, about thirty miles west of Detroit, began

limited parts production in November 1941. By the time the United States

entered the war, however, no part of the factory was complete. The main

building and the flying field were not completed until early 1942. But

the plant, except for the relatively small area where parts production

was underway, was in a state of turmoil as tools were received, fixtures

set up and supervisors and untrained employees tried coping with an

alien undertaking. The task was aggravated by a severe housing shortage

near the Willow Run vicinity and the length of time required—an hour

or more each way—for Detroit workers to commute to and from their

jobs.

Willow Run’s problems

were ignored or glossed over in the hundreds of newsstories and

editorials about the huge plant in early 1942. Instead, the press dwelt

on the size of the factory and the scope of its operations, referring to

it as the "most enormous room in the history of man," the

"largest building in the history of the world" and the

"mightiest wartime effort ever made by industry." The plant

was described as a "marvelous factory" by the Boston

American, an "amazing bomber plant" by the New York Sun;

a "U.S. miracle" by the nineteen newspapers of the

Scripps-Howard chain and by other publications as "Henry Ford’s

miracle," "one of the seven wonders of the world,"

"the greatest show on earth" and as the "damndest

colossus the industrial world has ever known." Dozens of newspapers

declared that Willow Run spelled ruin for the Axis countries. "It

is a promise of revenge for Pearl Harbor," said a Detroit paper.

"You know when you see Willow Run that in the end we will give it

to the Japanese good."

If praise of the plant

itself indicated that Ford had wrought yet another miracle, statements

and forecasts about how soon and how many bomber would flow from the

facility confirmed this impression a hundredfold. Most press reports

stated that B-24s would roll off the assembly line "before June

1." A radio broadcast beamed to Manila Bay, Philippines, in

February 1942, reported that Ford was already producing

"astronomical" numbers of planes for the U.S. Army Air Corps.

The broadcast spurred embattled American and Filipino troops on the

Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor Island to start a "Bomber for

Bataan" fund; some servicemen pledged a month’s pay to the futile

enterprise.

Many of the stories about

Willow Run reported that the plant, once production began, would build

bombers at the "unprecedented" and "unbelievable"

rate of "one every two hours," "one per hour,"

"two per hour," "dozens daily," "en masse"

and "one every few minutes," just like cars. (Compare these

figures to the 169 B-24s built in 1941 by the plane’s designer.

Consolidated Aircraft.) Several publications even reported that 1,000

B-24s would emerge from the factory every twenty-four hours. The most

exaggerated estimate of the plant’s future production appeared in the

usually conservative New York Herald Tribune, which

boasted, "Willow Run annually will produce planes by the tens of

thousands and eventually, if required, by the hundreds of

thousands."

These statements were

premature and highly inaccurate. Willow Run did not produce a plane

until July 1942, and that one was a knockdown sent to a Douglas Aircraft

assembly plant in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The first flyaway was not turned over

to the United States Army until September 10, 1942.

The Ford Motor Company

should have refuted the statements or at least cautioned against

overoptimism. It did neither, and the paeans of praise continued

unabated. Some of the plaudits were initiated by starry-eyed visitors to

the plant. The president of Peru told reporters, "This plant is

wonderful . . . It will bring quick victory." Captain Randolph

Churchill, son of the British prime minister, assured the press that

"if Adolf Hitler could see Willow Run, he’d cut his throat right

now." Sir Oliver Lyttleton, Britain’s minister of production,

noted that if Hitler and Goering visited Will Run they "Would have

thrown in their hands, or blown out their brains." He concluded,

"Five men with the imagination of Henry Ford would end this war

within a period of six months."

The myth that Willow Run

was performing production miracles exploded in August 1942 when James H.

"Dutch" Kindelberger, the blunt president of North American

Aviation, told a startled group of reporters that Willow Run, despite

all of the talk, had yet to manufacture an airplane.

Kindelberger’s statement

was quickly picked up and expanded on "The March of Time," a Time

magazine-sponsored national radio newscast, and in Time’s

sister publication, Life. Although pressed to deny or confirm the

charges made by Kindelberger, inexplicably neither the Ford company nor

the War Department offered immediate comment. The press, led to believe

that Willow Run was building complete bombers (at the rate of one per

hour, according to some reports), was baffled.

The press remained

perplexed and was barred from the plant until November. By then planes

were being built, both knockdowns and flyaways, and net production

totaled fifty-six. Meanwhile, in September President Franklin Roosevelt

and his wife, Eleanor, secretly toured Willow Run. Following the visit

the Office of Censorship issued conflicting reports on whether or not

the president had seen bombers in production.

In January 1943 the

government’s War Production Board officially criticized Willow Run’s

performance for the first time. The factory’s primary problem,

according to the board, was a shortage of manpower, the plant found it

difficult to hire and keep competent workers.

The board’s report

unleashed a barrage of criticism, leading many people across the country

to call the plant "Willit Run?"—a name allegedly coined by

rival aircraft manufacturers. This criticism prompted Senator Harry

Truman, chairman of the Senate Committee Investigating the National

Defense Program, to conduct an immediate inquiry into Willow Run

production. "There has been so little production," snapped

Truman, "as to amount to virtually none."

Criticism notwithstanding,

Willow Run’s production was mounting—31 planes in January 1943, 75

in February, 148 in April and 190 in June. The press was congratulatory.

"At long last," declared Business Week, "America

is finding its faith in Henry Ford and Willow Run reestablished. And

this time it rests on the solid fact of bomber production." In

April Charles E. Wilson, vice-chairman of the War Production Board, told

reporters after touring Willow Run that the plant was "on the beam

. . . The Willow Run plant will be turning out 500 planes a month by the

time the next snow flies." Unfortunately, the day after Wilson’s

visit snow fell in Detroit.

On July 10 the Truman

committee issued its long-awaited findings on Willow Run. The report

acknowledged that "some delay had to be expected" in building

a large number of "huge and complicated" airplanes such as the

B-24. But it also was critical of Willow Run’s performance, which

fueled rumblings of dissatisfaction; in September the Army Material

Command suggested the government unseat Henry Ford and take over the

management of the factory.

During the last few months

of 1943, as the giant plant began living up to its press notices of 1941

and the first half of 1942, the threat of a government takeover faded.

Bomber production, which stood at 190 in June 1943, increased to 231 in

August, 308 in October and 365 in December. In October a War Production

Board report on the aircraft industry revealed that "whereas Willow

Run was one of the poorest producers last Fall it is now one of the

best." The report added that "production per man at Willow Run

has risen about 40 times in the last year."

As the plant entered a

period of glory in 1944 its production reports were impressive. In March

Willow Run produced its three thousandth bomber. On April 16 Ford

announced that Willow Run, starting that previous February, had achieved

its long-sought goal—the production of "approximately one bomber

an hour." By July 1 Willow Run had built five thousand bombers,

half of them in the first six months of 1944. At the same time, it was

reported that "the automotive type precision tooling at Willow Run

had resulted in such uniformity of production that more than half of all

of the Ford-built Liberators were accepted for delivery on their maiden

flights," an unusually high percentage of plane approval.

As many of the early

production boasts of Ford spokesmen and the press began coming true, the

plant and company officials were lauded to the skies. In April 1944

Senator Truman, after visiting the bomber plant, called Henry Ford

"the production genius" of the United States. In mid-April,

following the announcement of the bomber-per-hour production rate,

dozens of newspapers hailed Willow Run as "the war production

miracle that has been wrought in Detroit" and as the plant that

furnished "a sky-full of bombers to wreck the Nazi war

machine." Henry Ford was accorded similar praise. "His

achievement is tremendous," declared the Asheville (North

Carolina) Citizen in a representative editorial. "He

symbolizes the remarkable industrial techniques which have made this

nation one vast armory."

During the remainder of

1944 and through 1945 hundreds of stories on Willow Run appeared in

newspapers and magazines. Many of the phrases used to describe the plant

were as effusive as, and reminiscent of, those published during the

first half of 1942—"a symbol of American ingenuity," a

"magnificently-tooled colossus," a "product of inventive

genius," "one of the world’s great monuments of production

genius," a "production miracle" and the "miracle

production story of the war."

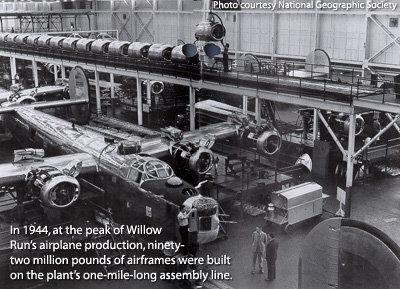

In 1944, Willow Run’s

peak production year, the plant built 92 million pounds of airframes,

far more poundage than had ever poured out of any one plant in one year

and 4.6 percent of all U.S. airframe production during the years

1940-44. Willow Run ’s 1944 airframe production almost equaled Japan’s

total airframe poundage for that year—and was approximately half that

of either Germany, Great Britain or the Soviet Union. Moreover, the

factory’s assembly-line production methods permitted Ford to deliver

Liberators to the government for $137,000 each in 1944, compared to

$238,000 two years earlier.

The plant’s highest

monthly bomber output, 428, was attained in August 1944. After

September, when the plant was geared to make 650 bombers a month (or

9,000 planes per year) it did not produce to its fullest capacity (the

War Department having ordered cutbacks on B-24 production in favor of

building the larger B-29 and B-32 bombers at other factories).

The total number of B-24s

built at Willow Run was 8,685. The last bomber, named the "Henry

Ford," moved off the assembly line on June 24, 1945. A few minutes

before the plane was to be towed from the plant, Henry Ford requested

that his name be removed from the nose of the ship and that employees

sign their names in its place.

Although Ford contributed

far less to the overall war effort than General Motors (GM), the public

believed that he had done more to win the war than GM or any other

automobile company. A national sample of public opinion by Elmo Roper in

July 1944 showed that 31 percent of the American people believed that

Ford was contributing more to the war effort than any other automaker,

as opposed to 21 percent for GM. In the spring of 1945 Roper found that

Henry Ford ranked second only to Henry J. Kaiser, a major West Coast

shipbuilder, as the man to have done more to win the war than any other

American, not counting Presidents Roosevelt and Truman and military

figures Ford received approximately twice as many votes as the men

ranked third and fourth in the pool. Donald M. Nelson, chairman of the

War Production Board, and James F. Byrnes, director of war mobilization.

In reality, Henry Ford’s

contribution to his company’s war effort was limited, and later was

said to be nil by Ford’s top manufacturing executive, Charles

Sorensen. Sorensen’s view, according to Sorensen, was shared during

the war by highly-placed Washington officials including Charles E.

Wilson and President Roosevelt.

Ford undoubtedly gave more

attention to Willow Run than any other of his wartime plants. But his

contribution to Willow Run’s success is debatable. Edsel Ford said in

1943 that his father "put a lot of his ideas" into the

project. Conversely, Sorensen countered that the octogenarian was simply

"the glorified leader" and "had nothing to do with the

program." He would, said Sorensen, "have a look at how things

were going on at Willow Run, but talk about its problems went in one ear

and out the other."

What is certain is that

Ford approved the idea of building the plant, passed on major policy

decisions affecting it and had a keen interest in its construction and

efforts to move it into production. He was a frequent, almost daily,

visitor to the factory during the first two years of the war. Numerous

photographs show him inspecting assembly lines and crawling under and

around B-24s. He also fretted incessantly over the delays in bomber

production.

The statement by the head

of a California aircraft plant that "Ford would drop $100 million

to get his bombers out" probably was a correct assessment of the

magnate’s attitude toward the B-24 program. Ford’s pride was hurt

when the press referred to his plant as "Willit Run?"; he was

vastly pleased when in late 1943 the factory refuted its critics. In

Willow Run’s banner year, 1944, when Ford’s physical and mental

health perceptibly deteriorated, he was seen less frequently at the

plant. The following year his precarious health prevented him from

attending the ceremony marking the end of bomber production. All factors

considered, Sorensen’s evaluation of Ford’s contribution to the

bomber effort seems harsh but not unjust. Willow Run was a miracle

plant, but Henry Ford was not a miracle man, and the wartime belief that

he was is one of the great myths of World War II.

Neither the Ford Motor

Company, nor any other person or company won the homefront war

single-handedly A massive team effort was required, and perhaps the

greatest heroes of all, at least in the aggregate, were the millions of

workers who toiled in defense plants across the nation.

World War II, as we look

back on it, seems somewhat larger than life. It was a time of heroes,

miracles and myths, both on the battlefield and on the home front. Both

America’s productive capacity and its people were tested as never

before—or since. Every important test was met by companies like Ford

and by millions of ordinary people who produced the materials of war and

filled homefront needs.

Today, most Americans look

back with satisfaction and pride, perhaps even with some nostalgia, on

World War II’s great homefront achievements. That is because no other

county, friend or foe, came close to matching the homefront heroics—and

miracles—of America in the "Big One."

This article first

appeared in the September/October 1993 issue of Michigan History.

|

Touring

Willow Run

Once production began at Willow Run, visitors flocked to tour

what one newspaper called "the damndest colossus the

industrial world has ever known." Unabashedly proud of

Willow Run, Henry Ford often hosted celebrities including politicians,

generals and movie stars.

Photos The Henry Ford |

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (far left) September 18, 1942 |

Representative Clare Booth Luce and other members of the

House Military Affairs Committee November 1943 |

General James Doolittle (center) and Ford's son, Edsel

May 29, 1942 |

Eddie Rickenbacker (far left) January 22, 1943 |

French General Henri Giraud

July 15, 1943 |

Vice-president Henry A. Wallace

July 24, 1943 |

U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (left) and Ford

Motor Company production chief Charles Sorensen (center) 1943 |

|