Three

of the cards of the traditional tarot depict cardinal virtues:

Strength (Fortitude), Temperance, and Justice. The fourth virtue,

Prudence, is mysteriously absent, although she appears in the

extended 97-card Minchiate deck.

Three

of the cards of the traditional tarot depict cardinal virtues:

Strength (Fortitude), Temperance, and Justice. The fourth virtue,

Prudence, is mysteriously absent, although she appears in the

extended 97-card Minchiate deck.

Three

of the cards of the traditional tarot depict cardinal virtues:

Strength (Fortitude), Temperance, and Justice. The fourth virtue,

Prudence, is mysteriously absent, although she appears in the

extended 97-card Minchiate deck.

Three

of the cards of the traditional tarot depict cardinal virtues:

Strength (Fortitude), Temperance, and Justice. The fourth virtue,

Prudence, is mysteriously absent, although she appears in the

extended 97-card Minchiate deck.

Although they were thoroughly Christianized in the Middle Ages, the cardinal virtues actually go back to the Greek philosophers. Aristotle treated them as examples of the idea of the mean as an ethical principle: we err when we go to extremes, but are virtuous when we strike the proper balance. Both Justice and Temperance are thus depicted with symbols of equilibrium (scales and two vessels in opposite hands).

These virtues are "cardinal" because they are four in number, connecting them with other quaternities such as the points of the compass, the seasons of the year, and the four elements. Four is the number of the material world, and the cardinal virtues are virtues of worldly, civic life. Given their classical pagan roots, they could hardly be otherwise. In Christian thought they were joined by three higher theological virtues (three being the number of the Holy Trinity), as identified by St. Paul: Faith, Hope, and Charity (or Love). These also appear in the Minchiate deck.

There were many variant orderings of the trump cards in the early centuries of the tarot in Italy. The placement of the virtues was one of the main variables - every community that adapted and altered the tarot apparently felt at liberty to rearrange the virtues. (In contrast the sequence Devil - Tower - Star - Moon - Sun was never altered at all!) In the southern tradition (Bologna, Florence, Rome, and Sicily), all three virtues were grouped together, though never in exactly the same internal order or in exactly the same spot with respect to the other cards. In the eastern tradition (Ferrara and Venice), a peculiar alteration was made. Justice was elevated to near the top of the tarot sequence, inserted between the Angel (Judgment) and the World. In this position, the card brings to mind the image of St. Michael, with sword and scales, weighing souls on Judgment day and vanquishing evil from the world. This leaves Fortitude and Temperance alone in the lower reaches, typically with Temperance conquering Love and Fortitude conquering the Chariot.

The most intriguing arrangement of the virtues, however, is in the Tarot de Marseille, which follows an arrangement presumably devised in Milan in the 15th century. Here the virtues are separated, but placed spaced three cards apart: Justice 8, Fortitude 11, Temperance 14. This has the interesting effect of placing Temperance between Death and the Devil, where she seems to provide a premonition of hope (the Star is 17!) in the midst of darkness.

Waite

swapped the placement of Strength and Justice, without historical

precedent, in order to make a better fit with the astrological

correspondences he used. It is a testimony to the influence of the

Waite-Smith deck that this order is often felt to be "standard" and

is used even in tarots that depart radically from the Waite-Smith

deck in other respects. The lemniscate and garland are also occultist

introductions, although the lemniscate was inspired by the shape of

the lady's hat in the Tarot de Marseille.

Waite

swapped the placement of Strength and Justice, without historical

precedent, in order to make a better fit with the astrological

correspondences he used. It is a testimony to the influence of the

Waite-Smith deck that this order is often felt to be "standard" and

is used even in tarots that depart radically from the Waite-Smith

deck in other respects. The lemniscate and garland are also occultist

introductions, although the lemniscate was inspired by the shape of

the lady's hat in the Tarot de Marseille.

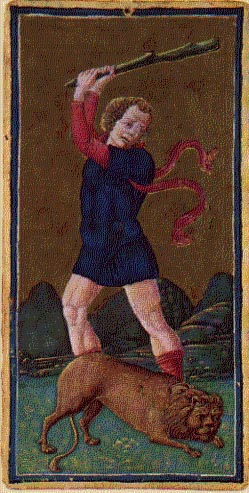

The title "Strength" is a translation of the French title "La

Force", which appears on the Tarot de Marseille cards. This probably

reflects a fading understanding that the picture depicted the virtue

Fortitude (the card is called "La Fortezza", or Fortitude, in the old

Italian sources). There are two distinct modes of depicting the

Fortitude in the tarot. In the version that was predominant in most

of the early Italian decks, we see a lady holding a large stone

column, perhaps breaking it. In the Tarot de Marseille and its

descendants,

we find a figure (usually but not always female) subduing a lion. The

Tarocchi del Mantegna, made in Ferrara around 1470, gives us both

column and lion! Brian Williams has noted that the image of Fortitude

as a serene woman, passively subduing a lion without apparent

physical effort, is very rare outside the tarot. The lady passively

holding the column is common, as is the image of a man (Hercules or

Daniel) wrestling a lion. He conjectures that the Tarot de Marseille

image is an inadvertent hybrid between these two common motifs,

combining the passive, feminine figure from the one tradition with

the lion from the other. The result has a strange psychological depth

to it that more than makes up for its superficial illogic.

descendants,

we find a figure (usually but not always female) subduing a lion. The

Tarocchi del Mantegna, made in Ferrara around 1470, gives us both

column and lion! Brian Williams has noted that the image of Fortitude

as a serene woman, passively subduing a lion without apparent

physical effort, is very rare outside the tarot. The lady passively

holding the column is common, as is the image of a man (Hercules or

Daniel) wrestling a lion. He conjectures that the Tarot de Marseille

image is an inadvertent hybrid between these two common motifs,

combining the passive, feminine figure from the one tradition with

the lion from the other. The result has a strange psychological depth

to it that more than makes up for its superficial illogic.

The Visconti-Sforza cards provide a very early example of an active, masculine Strength: a man is seen subduing a lion with a club. This card was not made by Bonifacio Bembo, the Milanese painter who created most of the set. It lacks the sweetness and poise of the Bembo cards. Along with several others, it was apparently made in Ferrara as a replacement for a lost card, or because Bembo's studio was for some reason unable to complete the project. The serene female figure is seen consistent throughout the centuries of the Tarot de Marseille, being found in the 17th-century Jacques Vieville tarot, and persisted with little change into the 19th century (see, for example, the Jean Proche tarot made in Switzerland in 1804).

The male figure reappears in the 19th century, however, in the "Neoclassical Tarot" luxury deck made by Gumppenberg in Milan in 1810, and in the engraved Swiss 1JJ designs which appeared somewhat later. (There are a few interesting similarities between the Gumppenberg luxury tarots and the Swiss 1JJ designs, suggesting some influence between the two.)

My personal favorite rendition of Strength is found in the

Tarocchino Milanese, a pattern launched by the "Soprafino" Tarot of

Carlo Dellarocca, first published by Gumppenberg in 1835. Here the

maiden breaks her  serene

pose and straddles the lion, looking both vigorous and determined.

She's opted for the "direct approach", reminding us that if you want

to subdue a lion you need to get in their and stomp some paw.

serene

pose and straddles the lion, looking both vigorous and determined.

She's opted for the "direct approach", reminding us that if you want

to subdue a lion you need to get in their and stomp some paw.

In Aristotle's thought, Fortitude represents moderation in our responses to fear and pain. The virtuous person neither seeks out danger nor avoids it at all cost, but instead courageously faces danger when necessary to achieve a higher goal. To endure the difficult, to stand firm against opposition, and to master one's fears--these are the tasks of Fortitude. Modern interpretations of the card sometimes stress the idea of the spirit controlling the urges and passions of the body. In the classical understanding of the virtues, this is a concept more at home with Temperance than with Fortitude.

In the Tarot de Marseille ordering, in which the virtues are spaced three apart, I like to think of each virtue mediating and transcending the two cards that precede it. In this vein, I see the Hermit as representing passivity, withdrawal, and letting the world pass one by--ideas that are not completely at odds with the early conception of the card as "The Old Man" or "Time", for indeed age often brings with it resignation or incapacity. The Wheel of Fortune is the opposite extreme: intense identification with each new twist and turn in life; ambition to the point of foolishness. The contrast is captured neatly in John Lennon's "Watching the Wheels". So there is the dilemma: to jump on the wheel and likely get ground into the dirt soon enough, or to withdraw and leave the fight to others? Fortitude is the virtue we need to answer this question and transcend it. She offers the determination, the strength of character, needed to pick one's battles and see them through, riding out the ups and downs and enduring disappointments without being defeated by them. By looking past the battle to the goal, she incorporates some of the Hermit's wisdom and detachment, but by courage she stays on the Wheel, participating in life and not merely waiting for Time to overtake her. Introversion and Extroversion in balance.

Return to the Histories of the Trump Cards