IN THE BEGINNING

The Epiphone story does not follow a straight line. For

more than a century, it has twisted and turned through triumph, setback and

comeback; hitting both dizzying highs and crushing lows as it winds its

way through the ages. The

latest chapter, in 2007, finds Epiphone as one of the most successful and

respected instrument manufacturers on the planet. The opening chapter begins

some 130 years before that, in the workshop of Anastasios Stathopoulo. way through the ages. The

latest chapter, in 2007, finds Epiphone as one of the most successful and

respected instrument manufacturers on the planet. The opening chapter begins

some 130 years before that, in the workshop of Anastasios Stathopoulo.

The son of a Greek timber merchant, Anastasios would not

follow his father into the family trade, although his chosen profession would

use the same materials. He began crafting lutes, violins and traditional

Greek lioutos in 1873. A few years thereafter, Anastasios sailed across the

Aegean Sea with his family to start a new life in Turkey. By 1890, his talent

and reputation had allowed him to open an instrument factory and start a

family. First to arrive in 1893 was a son, Epaminondas, followed later that

decade by Alex, Minnie and Orpheus.

By 1903, the persecution of Greek immigrants by the native

Turks had forced the Stathopoulo family to move again; this time to a residence

in the lower Manhattan neighborhood of New York. With Anastasios crafting

and selling his instruments on the ground floor, and the family living directly

above, the line between work and home life became increasingly blurred.

Epaminondas (known as 'Epi') and Orpheus ('Orphie') were soon helping out

in the shop and learning the business from the ground up.

And business was good. It was Anastasios' good fortune

to arrive in New York at the height of the mandolin craze, and this dovetailed

with the popularity of

his traditional Greek instruments amongst the city's bustling community.

Thanks to the success of their father's instruments (now labelled 'A.

Stathopoulo, manufacturer-repairer of all kinds of musical instruments',

and built in a warehouse on 247 West 42nd Street), the Stathopoulo children

enjoyed a privileged upbringing and a good education. But all that changed

in July 1915, when Anastasios died at the age of 52 from carcinoma of the

breast.

EPI TAKES CHARGE

Epi was just 22 when he took charge of the family business.

He inherited many of his father's strengths - including a keen business sense

and fierce pride in his work - but combined this with an awareness of the

changing times that would prove vital in the years to come. Crucially, Epi

was not just a luthier or a businessman. He was also a keen musician and

socialite.

Epi

respected the tradition of his father's instruments, but recognized the

importance of moving with the times. By 1917, he had changed the company's

name to the 'House Of Stathopoulo' and began adapting the product line. Mandolins

were falling out of favor. In the post-war era, banjos had started to boom

along with jazz, and Epi, with his ear to the ground, recognized this early

and armed his company to deal with it. Not only did Epi introduce a line

of banjos, but he also developed the instrument's design, patenting his own

tone ring and rim construction. It was a sign of things to come. Epi

respected the tradition of his father's instruments, but recognized the

importance of moving with the times. By 1917, he had changed the company's

name to the 'House Of Stathopoulo' and began adapting the product line. Mandolins

were falling out of favor. In the post-war era, banjos had started to boom

along with jazz, and Epi, with his ear to the ground, recognized this early

and armed his company to deal with it. Not only did Epi introduce a line

of banjos, but he also developed the instrument's design, patenting his own

tone ring and rim construction. It was a sign of things to come.

And

so, while the market shift caused some companies to flounder, the House Of

Stathopoulo flourished. The firm's structure was re-organized in 1923 as

its success snowballed (Epi made himself president and general manager) and

even its name was revised to reflect its changing identity. This was the

age of possibility, and Epi needed a brand to match. He eventually settled

on an amalgamation of his own nickname and a derivation of the Greek word

for 'sound'. It was the birth of Epiphone. And

so, while the market shift caused some companies to flounder, the House Of

Stathopoulo flourished. The firm's structure was re-organized in 1923 as

its success snowballed (Epi made himself president and general manager) and

even its name was revised to reflect its changing identity. This was the

age of possibility, and Epi needed a brand to match. He eventually settled

on an amalgamation of his own nickname and a derivation of the Greek word

for 'sound'. It was the birth of Epiphone.

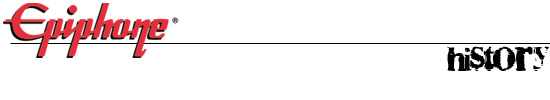

In 1924, Epiphone released the Recording Series of banjos

to universal acclaim. Indeed, the Deluxe, Concert, Bandmaster and Artist

models (plus the budget Wonder model) were so popular that by the following

year, Epi had expanded production and bought out the Favoran banjo firm to

cope with demand. Thanks to models like the Emperor, and the endorsement

of players like Carl Kress, this side of the business continued to grow along

with Epiphone's reputation, to the point where the company's name was changed

once again in 1928. For now, it would be known as the Epiphone Banjo

Company.

THE FIRST GUITARS

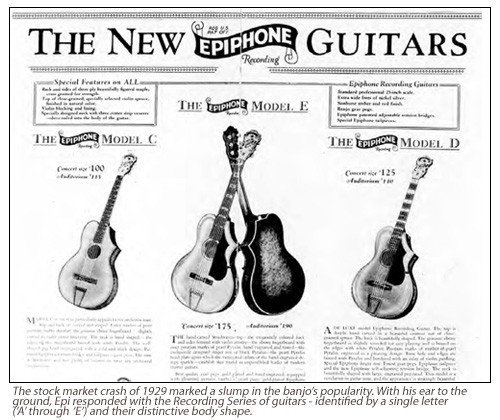

The stock market crash of 1929 drew a line under the age

of prosperity. Combined with the sudden slump in the banjo's popularity,

it sounded the death knell for many instrument manufacturers. Once again,

Epi was ready for the change. At the height of the banjo boom in 1928, he

had introduced the Recording series of guitars, each one identified only

by a letter ('A' through 'E') and notable for their unusual body shape. The

Recording guitars were a combination of spruce and laminated maple, with

either an arched or flat top, depending on the price.

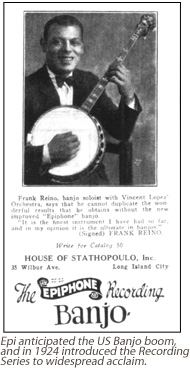

The market was certainly ripe, but the Recording guitars

were not a success. One problem was a lack of celebrity endorsement. The

other was a lack of volume. The Recording guitars were too small and arguably

too ornate, particularly in comparison to the mighty size and volume of the

Gibson L-5. At least Epi was taking notes. It wasn't hard to see the L-5's

influence on the new Epiphone archtops that followed

in 1931, with the Masterbilt Series sharing similar f-holes, pegheads, and

even a similar name to the Gibson Master Model range (though the individual

model names would be more interesting than Gibson's serial number system,

including the DeLuxe, Broadway, Windsor and Tudor). Despite taking inspiration

from Gibson, however, the Masterbilts had their own identities. Their intention

was not to emulate the Master Model range, but to destroy it.

EPIPHONE VERSUS GIBSON

Throughout the 1930s, the rivalry between Epiphone and

Gibson would veer from friendly sparring to all-out warfare. Slighted by

the introduction of the Masterbilts, and having emerged from its commercial

slump at the

start

of the decade, Gibson returned fire in 1934 by increasing the body width

of its existing models and introducing the king-size Super 400 (named after

its $400 price tag). Not to be outdone, Epi replied the following year with

the top-of-the-line Emperor, which raised the stakes with a slightly wider

body and a provocative advertising campaign featuring a semi-naked woman.

In 1936, Epiphone struck again, increasing the size of its De Luxe, Broadway

and Triumph models by an inch (making them 3/8" wider than the Gibsons). start

of the decade, Gibson returned fire in 1934 by increasing the body width

of its existing models and introducing the king-size Super 400 (named after

its $400 price tag). Not to be outdone, Epi replied the following year with

the top-of-the-line Emperor, which raised the stakes with a slightly wider

body and a provocative advertising campaign featuring a semi-naked woman.

In 1936, Epiphone struck again, increasing the size of its De Luxe, Broadway

and Triumph models by an inch (making them 3/8" wider than the Gibsons).

By this point, Epiphone guitars were considered to be

amongst the best in the world, and Epi himself was enjoying the patronage

of some of the most respected players on the scene. The Epiphone showroom

- now returned to its early location on West Street, Manhattan - was both

the company's HQ and a hangout for famous musicians. On Saturday afternoons,

Epi would simply open the display cases and allow legends-in-waiting like

Al Caiola and Harry Volpe to jam for the benefit of the people watching on

the pavement outside. Perhaps this wasn't just an act of benevolence: both

players would later go on to endorse Epiphone instruments, along with many

others including Les Paul.

Epiphone wasn't just gunning for Gibson. Growing aware

of the success of Rickenbacker's electric models since 1932, Epi made his

move on this new market with the introduction of the Electar Series (originally

known as Electraphone) in 1935. The design was strong, with individually

adjustable polepieces on the 'Master Pickup' giving optimum output, and while

Gibson had evidently been thinking the same thing (by the following year

they had introduced an electric Hawaiian guitar), the Electar line landed

a serious blow on Epiphone's rivals, while consolidating their own reputation

as innovators. By the summer of 1937, Epi reported that sales had

doubled.

As the decade played itself out, the rivalry between Epiphone

and Gibson showed little sign of abating. In 1939, the two firms introduced

similar 'pitch-changing'

Hawaiian guitar designs. That same year, Gibson introduced a line of violins,

while Epiphone struck back with a series of upright basses. It took the outbreak

of the World War II, and the shutdown of US guitar production, to ring the

bell on the bloodiest luthier boxing match of the age. similar 'pitch-changing'

Hawaiian guitar designs. That same year, Gibson introduced a line of violins,

while Epiphone struck back with a series of upright basses. It took the outbreak

of the World War II, and the shutdown of US guitar production, to ring the

bell on the bloodiest luthier boxing match of the age.

HARD TIMES

The war changed everything. Before the bombing of Pearl

Harbour in 1941, Epiphone had been riding on the crest of a wave. When the

last of the fighting ended in 1945, the company found itself without its

greatest asset. Tragically, Epi had died of leukemia during the war, meaning

that Epiphone was handed down to younger brothers Orphie and Frixo, who would

respectively be responsible for the financial and mechanical running of the

operation.

The problems weren't obvious to start with. Epiphone continued

to clash with Gibson via the introduction of cutaway versions of the Emperor

and De Luxe, and raised the bar considerably with the arrival of the electric

cutaway De Luxe. Pickups continued to be refined, and famous players continued

to appear onstage armed with Epiphone guitars. From the outside, it seemed

to be business as usual.

But cracks soon appeared, both on the production line

and in the boardroom. The Stathopoulo brothers were not getting along, and

in 1948, Frixo offloaded his share to Orphie. Worse, the company was losing

the reputation for craftsmanship and innovation built up during Epi's reign,

and the pressures for unionization compounded the problems. To sidestep this

last issue, the Epiphone factory moved from Manhattan to Philadelphia in

1953, but the fact that many of the firm's craftsmen refused to leave New

York resulted in a drop in quality and the very real danger of

bankruptcy.

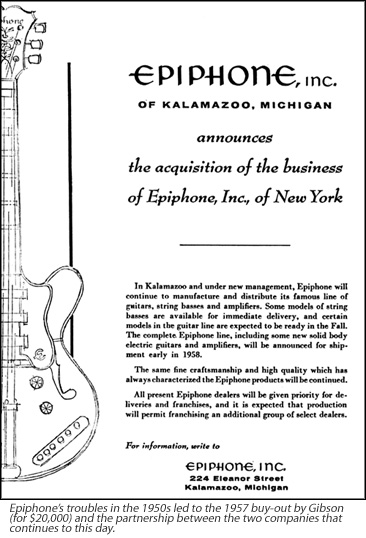

THE UNION OF EPIPHONE AND GIBSON

While Epiphone's problems got worse as the 1950s progressed,

Gibson was going from strength to strength. Its main competition now came

from  the California-based

Fender Company, creator of the Telecaster and Stratocaster models that had

been released earlier that same decade. If Gibson had a weakness, it was

that their upright bass production had stopped before the war and never started

again. So when Gibson's general manager, Ted McCarty, received a call from

Orphie asking whether he'd be interested in buying out the Epiphone bass

business (still a hugely respected division of the company, despite its

troubles), he didn't need asking twice. McCarty paid the $20,000 asking price

and Gibson took control of Epiphone in May 1957. the California-based

Fender Company, creator of the Telecaster and Stratocaster models that had

been released earlier that same decade. If Gibson had a weakness, it was

that their upright bass production had stopped before the war and never started

again. So when Gibson's general manager, Ted McCarty, received a call from

Orphie asking whether he'd be interested in buying out the Epiphone bass

business (still a hugely respected division of the company, despite its

troubles), he didn't need asking twice. McCarty paid the $20,000 asking price

and Gibson took control of Epiphone in May 1957.

Gibson's original intention was to harness the reputation

of the Epiphone bass line. By 1957, this plan had been scrapped. Instead,

McCarty wrote in a memo that year, the Epiphone brand would be revived and

a new line of instruments created. These Gibson-made Epiphones would then

be offered to dealers who were keen to win a Gibson contract, but still earning

their stripes (the right to sell Gibson models was hotly contested between

dealerships at this time). It was the perfect solution. Dealers would get

a Gibson-quality product, without treading on the toes of the traders who

already sold the real thing. The Epiphone operation was relocated to Kalamazoo

(the same city as Gibson HQ) and work began.

A NEW BEGINNING

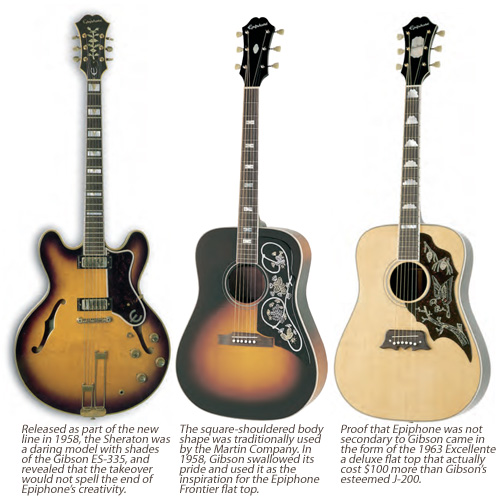

Epiphone wouldn't stay in the shadow of Gibson for long.

When the new line started filtering through in 1958, it became clear that

the brand now had three separate identities. On one hand, Epiphone now listed

budget-conscious versions of existing Gibson models. Alongside this, however,

there were also recreations of classic Epiphone designs (such as the Emperor,

Deluxe and Triumph) and a selection of new models that had never been seen

before. These included electrics like the semi-hollow Sheraton and the

solid-bodied Moderne Black (alongside a double-cutaway model inspired by

the Telecaster), and flat-top acoustics like the Frontier, whose

square-shouldered body style was a first for Gibson (it was traditionally

a Martin design). Combined with the introduction of amplifiers, it was becoming

clear that Epiphone instruments would be far more than the 'sort of almost

Gibsons' many had predicted.

The grand unveiling of the Epiphone line took place at

the NAMM trade show in July 1958, with an electric Emperor as the flagship

model. The show itself would generate orders of 226 guitars and 63 amps (a

modest return), but over the next few years Epiphone would get into a swagger,

shifting 3,798 units in 1961, and accounting for 20% of the total units shipped

out of Kalamazoo by 1965. Even more impressive was the prestige of the guitars

themselves. In the early 1960s, the Epiphone Emperor cost significantly more

than the top-of-the-range Gibson Byrdland, while 1963's deluxe flat top

Excellente was $100 more than the J-200, and made of rarer tonewoods.

The early 1960s brought the explosion of folk music, and

Epiphone was ready to cater to it. The firm reintroduced its Seville classical

guitar (with and without pickups) in 1961, and complemented this with the

Madrid, Espana and Entrada models. In 1962, Epiphone also started listing

a twelve-string guitar called the Bard, a smaller version known as the Serenader,

and (in 1963) a series of steel-string flat-topped folk guitars

including the Troubadour.

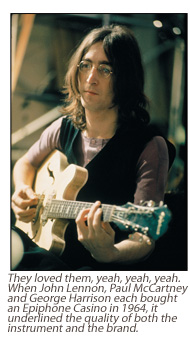

The strength of the acoustic range was matched by a number of electric classics,

like the double-cutaway Casino, and by the time the Beatles appeared with

three of these models (one each for John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George

Harrison), it seemed like the rubber stamp on Epiphone's recovery. The company

now listed fourteen electric archtops, six solid-bodied electrics, three

basses, seven steel-string flat tops, six classicals, four acoustic archtops,

three banjos and a mandolin. including the Troubadour.

The strength of the acoustic range was matched by a number of electric classics,

like the double-cutaway Casino, and by the time the Beatles appeared with

three of these models (one each for John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George

Harrison), it seemed like the rubber stamp on Epiphone's recovery. The company

now listed fourteen electric archtops, six solid-bodied electrics, three

basses, seven steel-string flat tops, six classicals, four acoustic archtops,

three banjos and a mandolin.

TURNING JAPANESE

The early to mid-1960s were boom time for Epiphone, with

unit sales increasing fivefold between 1961 and 1965. But the good times

couldn't  last forever.

The rise of foreign-made guitars had caught the US industry napping, and

by 1969, these cheap models (often based on existing American designs) had

stolen some 40% of the Epiphone/Gibson market share and closed many companies

down entirely. last forever.

The rise of foreign-made guitars had caught the US industry napping, and

by 1969, these cheap models (often based on existing American designs) had

stolen some 40% of the Epiphone/Gibson market share and closed many companies

down entirely.

There were other problems. Gibson manager Ted McCarty

had stepped down, the quality of the product was thought to have slipped,

and union problems were simmering again. In its weakened state, Gibson's

parent company CMI was bought in 1969 by the Ecuadorian ECL corporation (whose

experience was not in guitars, but beer) and Epiphone found itself in a

predicament - perceived to be secondary to Gibson, but too expensive to compete

with the foreign imports.

The idea of moving Epiphone production to Japan had actually

been floated before the ECL takeover. By 1970, it was a reality, with American

production grinding to

an abrupt halt and a new line of Epiphones being exported from the Japanese

town of Matsumoto. But these were not Epiphones as the world knew them. On

the contrary, they were just rebadged versions of models that were already

being produced by the Matsumoku Company - with little imagination or respect

for the company's pedigree. production grinding to

an abrupt halt and a new line of Epiphones being exported from the Japanese

town of Matsumoto. But these were not Epiphones as the world knew them. On

the contrary, they were just rebadged versions of models that were already

being produced by the Matsumoku Company - with little imagination or respect

for the company's pedigree.

Things had improved by 1976, when the Epiphone line was

bolstered by the appearance of models like the Monticello, a series of

scroll-body electrics, and the new Presentation range of flat tops. There

was also the Nova series of flat tops and three new solidbodies named Genesis.

By 1979, the Epiphone product list was gathering speed, with over 20 steel-string

flat tops, and plenty more besides.

THE MOVE TO KOREA

Just as Epiphone's Far Eastern operation seemed to be

finding its feet, three bombshells dropped in quick succession. The first

was the rise of the electronic keyboard. The second was the rising cost of

Japanese production, which led to Epiphone's relocation to Korea in 1983,

and collaboration with the Samick Company. The third took place in the Gibson

boardroom at the start of 1986, with three Harvard MBAs (Henry Juszkiewicz,

David Berryman and Gary Zebrowski) taking the company off the hands of

ECL/Norlin. Reviving Gibson was the priority for the new owners, and with

Epiphone making less than $1 million revenue in 1985, there seemed a danger

it would be swept under the carpet and forgotten.

But Epiphone was still buzzing with potential. Soon enough,

Juszkiewicz had identified it as a sleeping giant, and made the trip to Korea

to decide how it could be pushed to match the success of other Asian brands

like Charvel and Kramer. As he absorbed Epiphone's pedigree, Juszkiewicz

started getting results, and soon sales were growing again.

Sales weren't the only thing on the move. By 1988, the

Epiphone product line was evolving. Epiphone now listed a new PR Series of

square-shouldered acoustics, along with an interpretation of Gibson's J-180,

several classical guitars, a banjo and a mandolin. There was also a solid

selection of Gibson-derived instruments (from flagship models like the Les

Paul and SG to new archtops like the Howard Roberts Fusion) and a tip of

the hat to Epiphone's past in the form of the Sheraton II.

TAKING ON THE WORLD

It was a start. But as the 1990s rolled around, Epiphone

still had work to do. The line was more than comprehensive - offering 43

different models  across

a range of styles and budgets - but the lack of historic Epiphone products

needed to be addressed. The legendary instruments from Epiphone's past should

have been leading the company's charge into the future. Without them, Epiphone

was still seen by some as a faceless import; a fact reflected by its modest

global sales. across

a range of styles and budgets - but the lack of historic Epiphone products

needed to be addressed. The legendary instruments from Epiphone's past should

have been leading the company's charge into the future. Without them, Epiphone

was still seen by some as a faceless import; a fact reflected by its modest

global sales.

Taking charge of Epiphone around this time, David Berryman

identified the other problem that was stopping the firm from taking on the

world. It still didn't have its own dedicated office or workforce. Moving

fast, Berryman instigated the acquisition of an office in Seoul, appointed

Jim Rosenberg as product manager and set about addressing the misconception

that Epiphone was secondary to Gibson.

The Seoul office was a major turning point. Instead of

the long-distance relationship that the firm had previously had with its

product, Epiphone was now able to roll up its sleeves and muck in with the

dedicated quality control staff at the factory. During the long days and

sleepless nights that followed, the Epiphone product changed beyond all

recognition. Factory

processes were assessed

and refined. Manufacturers were visited and briefed on the components that

would make these instruments special, with Epiphone taking a hands-on role

in the development of everything - from pickups, bridges, toggle switches

and fret inlays to unique features like the metal E logo and frequensator

tailpiece. Financially and emotionally, Epiphone invested everything it had

in these new models. processes were assessed

and refined. Manufacturers were visited and briefed on the components that

would make these instruments special, with Epiphone taking a hands-on role

in the development of everything - from pickups, bridges, toggle switches

and fret inlays to unique features like the metal E logo and frequensator

tailpiece. Financially and emotionally, Epiphone invested everything it had

in these new models.

It paid off. One of the first fruits of Epiphone's labours

was a limited-edition run of electric-acoustics, and the success of these

confirmed how far the company had come. By the time of the 1993 NAMM show,

there were more thin-bodied electric-acoustics and a new range of PRs. It

all hammered home the impression that Epiphone was a leader rather than a

follower.

But Epiphone was looking to the past as well as the future.

In 1993, a limited run of Riviera and Sheratons were produced in Gibson's

Nashville factory, with the company's Montana plant also building 250 Excellente,

Texan and Frontier flat tops. These Epiphones were only intended as a special

event (it was impractical to move production to the US permanently) but the

public reaction prompted Rosenberg to reissue many classic designs via the

Korean range. Those who attended the 1994 NAMM witnessed the re-introduction

of legends including the Casino, Riviera, Sorrento and Rivoli bass. In the

months that followed, word spread, and guitar luminaries including Chet Atkins

and Noel Gallagher signed up to the Epiphone cause - confirmation that these

were instruments to be played through choice, not necessity.

ONWARDS AND UPWARDS

Epiphone

was arguably just as successful in the late-90s as at any point in its history.

With confidence booming, this era saw the launch of the Advanced Jumbo Series

and the release of several important signature models. The John Lee Hooker

Sheratons from the USA Collection were tasteful, toneful and utterly authentic.

The Noel Gallagher Supernovas had attitude and edge, and became some of the

most iconic designs of the time. Then there were the John Lennon 1965 and

Revolution Casinos. With their US birthright, unbeatable authenticity and

sense of aspiration, these models reunited Epi with the greatest artist of

all time, and underlined the company's own re-emergence as a rock

legend. Epiphone

was arguably just as successful in the late-90s as at any point in its history.

With confidence booming, this era saw the launch of the Advanced Jumbo Series

and the release of several important signature models. The John Lee Hooker

Sheratons from the USA Collection were tasteful, toneful and utterly authentic.

The Noel Gallagher Supernovas had attitude and edge, and became some of the

most iconic designs of the time. Then there were the John Lennon 1965 and

Revolution Casinos. With their US birthright, unbeatable authenticity and

sense of aspiration, these models reunited Epi with the greatest artist of

all time, and underlined the company's own re-emergence as a rock

legend.

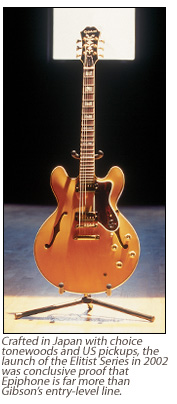

As the new millennium came and went, the momentum continued,

as Epiphone introduced the Elitist range and strengthened its position in

the acoustic market with the acquisition of veteran Gibson luthier Mike Voltz.

Voltz's

contribution to Epiphone's development cannot be overstated. While the firm

had revived its electric range to great acclaim, there was still a sense

that it needed to claw back its former reputation for world-beating flat

tops. All that changed with the introduction of the Masterbilt range, which

- along with the subsequent 2005 release of the Paul McCartney 1964 USA Texan

- consolidated Epi's acoustic credentials and reacquainted the firm with

two big names from its past. Voltz's

contribution to Epiphone's development cannot be overstated. While the firm

had revived its electric range to great acclaim, there was still a sense

that it needed to claw back its former reputation for world-beating flat

tops. All that changed with the introduction of the Masterbilt range, which

- along with the subsequent 2005 release of the Paul McCartney 1964 USA Texan

- consolidated Epi's acoustic credentials and reacquainted the firm with

two big names from its past.

By 2003, the international demand for Epiphones was such

that the company had opened a new factory in China. Not only did this mark

the first time that Epiphone had its own dedicated factory since the initial

takeover by Gibson but staffed by US managers and luthiers, it also armed

them with the control over their own product that would let them take development

to the next level, and give them a massive edge over the competition (most

of whom continued to share workspaces).

In

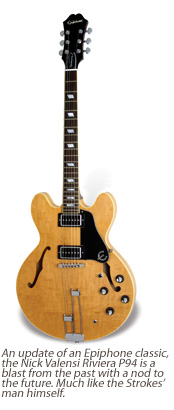

2007, Epiphone is all things to all players. Working musicians prize the

company for its Gibson replicas, offering the quality of the most famous

US models at competitive prices. Collectors of vintage guitars snap up the

authentic Elitist reissues of the Emperor, Casino and Excellente (and many

more). Recording artists turn to the Epiphone US range for quality that rivals

any guitar manufacturer in the world, while rock 'n' roll fanatics delight

in the company's signature models, which include everything from the Nick

Valensi Riviera to the Zakk Wylde Les Paul Customs. Regardless of budget,

ability or musical leaning, today's Epiphone line has it covered. In

2007, Epiphone is all things to all players. Working musicians prize the

company for its Gibson replicas, offering the quality of the most famous

US models at competitive prices. Collectors of vintage guitars snap up the

authentic Elitist reissues of the Emperor, Casino and Excellente (and many

more). Recording artists turn to the Epiphone US range for quality that rivals

any guitar manufacturer in the world, while rock 'n' roll fanatics delight

in the company's signature models, which include everything from the Nick

Valensi Riviera to the Zakk Wylde Les Paul Customs. Regardless of budget,

ability or musical leaning, today's Epiphone line has it covered.

Perhaps even more important, Epiphone has retained the

pioneering spirit that was always Epi Stathopoulo's calling card. Whether

through the 2006 'Guitar of the Month' scheme (offering a different collector's

model each month) or through its unending quest to challenge tradition, this

is still a firm that thrives on the risk while always delivering the result.

Perhaps David Berryman puts it best. "Gibson is a traditional company, Epiphone

is more of a renegade. It marches to the beat of a different drum. Always

has." One suspects that it always will.

EPIPHONE TIMELINE

1863 - Anastasios Stathopoulos is born in Sparta,

Greece to a local lumber merchant.

1873 - Anastasios builds his first instruments

(according to Epiphone literature of the 1930s).

1877

- The Stathopoulos family moves to Smyrna in Asiatic Turkey. 1877

- The Stathopoulos family moves to Smyrna in Asiatic Turkey.

1890 - Anastasios establishes a large instrument

factory in Smyrna which provides violins, mandolins, lutes and traditional

Greek lioutos.

1893 - Epaminondas (Epi) is born to Anastasios

and his wife Marianthe. His name is inspired by a military hero from ancient

Greek history.

1903 - Following persecution of Greek immigrants

by the native Turks, the Stathopoulos family moves to New York (during the

immigration process the final 's' is dropped from the family name). The family

now includes sons Alex and Orpheus (Orphie), and daughter Alkminie (Minnie).

Another son (Frixo) and daughter (Elly) are born in America.

1915 - Ansatasios dies, leaving Epi in charge,

and ushering in the new era of the Epiphone company (although this brand

name is still some years away). Orphie is second-in-command, while Frixo

and Minnie will later become active in the company.

1917 - Epi begins labeling instruments with the

House of Stathopoulo brand. The era of the tenor banjo is beginning, and

Epi is granted his first patent for banjo construction.

1924 - Combining his own name with the Greek word

for sound, Epi registers the Epiphone brand name.

1925 - Epi buys the Favoran banjo company in Long

Island City (across the East River from Manhattan) and launches the Epiphone

Recording line of banjos. Their ornate design and classic tone makes then

an instant success.

1928 - Buoyed by the success of the Recording banjos,

Epiphone introduces a Recording line of guitars, most of them carved tops

and spruce/maple tonewoods.

1931 - Epiphone introduces a full line of f-hole

archtop guitars (12 models in all), with the top models (the DeLuxe, Broadway

and Triumph) becoming familiar Epi model names for the next 40 years.

1935 - As the latest blow in the long-running

competition with Gibson, Epiphone launches the Emperor.

1937 - Epiphone unveils its innovative adjustable-pole

pickup (as part of the Electar series). By this point, the company's reputation

has led to endorsements from prominent players such as Tony Mottola, Dick

McDonough and George Van Eps.

1943 - Epi dies of Leukemia, leaving brothers Orphie

and Frixo in charge. Feuding between them leads Frixo to sell his stock in

1948. The company falls on hard times in the post-war years, and by the mid-50s,

Epiphone is making few instruments aside from upright basses and the Harry

Volpe student guitar.

1957 - Gibson's parent company, CMI, buys Epiphone

for $20,000, originally intending to harness its upright bass operation,

but ultimately reviving the Epiphone name on guitars. A full line of newly

designed acoustics and electrics is unveiled in 1958, and two years later

Epiphone production moves into Gibson's factory in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

1961 - Country superstar Ernest Tubb equips his

entire Texas Troubadours band with Epiphones, while Marshall Grant plays

upright Epi bass with Johnny Cash.

1963 - Longtime Epiphone endorsee Al Caiola gets

his own model, and plays it on his hit records of the themes from Bonanza

and The Magnificent Seven.

1964 - George Harrison, John Lennon and Paul McCartney

buy Casinos. Alongside All You Need Is Love (which features the three), McCartney

uses his Casino for the solos on Ticket To Ride, while Harrison uses his

for the famous runs on Hello Goodbye. McCartney also buys an Epiphone Texan,

which he plays on Yesterday.

1970 - In the face of foreign competition, Epiphone

production is moved to Japan. Through the 1970s and early '80s, the Epiphone

line has little continuity, although it maintains respect as a quality import

brand.

1983 - Epiphone production is moved to Korea.

1986 - Henry Juszkiewicz, David Berryman and Gary

Zebrowski acquire Epiphone and Gibson. The Epi line is soon expanded to include

traditional models like the Sheraton, Emperor and Howard Roberts, along with

Epi versions of Gibson classics like the Les Paul, Flying V and

Explorer.

1992 - Jim Rosenberg arrives as product manager

to head up the Epiphone line, and soon expands it to offer virtually every

style of guitar to the value-conscious player. The opening of a dedicated

office in Seoul allows Epiphone the hands-on relationship with its product

that had previously been lacking.

1993 - Epiphone's reputation is further enhanced

by the Nashville USA Collection, limited edition models that represent the

first US-made Epiphones for over 20 years.

1994 - Gibson's Montana division follows suit,

offering a limited edition US run of the Excellente, Frontier and Texan Epiphone

flat tops. The NAMM show of that year also witnessed the re-introduction

of classic designs including the Casino, Riviera and Sorrento (all part of

the new Korean range).

1996 - With Oasis at the peak of their popularity,

Epiphone build lead guitarist Noel Gallagher the iconic Supernova signature

model.

1998 - Epiphone introduce guitar and accessory

"starter-packages" while this period also sees the launch of the Advanced

Jumbo Series.

1999 - John Lennon Revolution and '65 Casinos are

launched as part of Epiphone's USA Collection, alongside a pair of John Lee

Hooker Sheratons. The sheer quality and flair of these signature models

underlines Epiphone's growing status as a brand to be played through

choice.

2002 - The new Elitist line is released to widespread

acclaim, while veteran Gibson luthier Mike Voltz is recruited by Epiphone

to focus on acoustic production and marketing. Voltz will prove instrumental

in establishing the new range of Masterbilt acoustics, a series that reunites

Epiphone with its past and consolidates the company's position as a leader

in both the electric and acoustic fields.

2003 - International demand leads to the opening

of a dedicated Epiphone factory in China. Staffed by US managers and luthiers,

it equips the company to support the growing popularity of its

instruments.

2005 - Epiphone is reacquainted with a big name

from its past, as the Paul McCartney 1964 USA Texan is re-introduced.

2007 - The modern Epiphone catalogue offers greater

diversity than ever, with new Elitist and signature models rubbing shoulders

with faithful reissues and authentic versions of the Gibson line. |