Post-Soviet Armies Newsletter An on-line database devoted to armed forces and power ministries

Jonathan Littell, "The Security Organs of the Russian Federation. A Brief History 1991-2004". Psan Publishing House 2006.

The Security Organs of the Russian Federation (Part III)

Yeltsin?s second term, throughout which, ill and alcoholic, he proved far weaker and isolated than during the first, was marked by his increasing reliance on the special services: three out of the four Prime Ministers he nominated after sacking Chernomyrdin came from the security organs, and he was only able to negotiate his exit in 1999 by fully handing over power to the siloviki. Before this, though, Russia would see a great deal of acrimonious intrigue, a catastrophic economic crisis, and even further fragmentation and corruption of its state bodies. The security services, caught up in the heart of these struggles, underwent relentless restructuration, which did little to improve their efficiency or capabilities. One result was that the number of generals was multiplied by seven as compared to the old KGB; at the same time, the quantity of experienced operational staff radically diminished: by 1995, only 20% of FSB officials had more than seven years of experience.1 The various agencies? leadership spent far more time struggling for political survival ? and in some cases, concentrating on their personal interests ? than they did trying to improve the work of their subordinates.

Terrorism of course remained on the agenda, and in 1997 an Interdepartmental Antiterrorist Commission, chaired by the Prime Minister, was set up to improve coordination between the services (see Fig. 4, above); judging on the basis of the second Chechen conflict, which began two years later, the effort does not seem to have borne much fruit. Chechnya itself was more or less pushed onto the back-burner and forgotten, though it was not entirely neglected by certain departments of the security organs. The main focus was the economy. In February 1997, the FSB?s Kovalev went to the Davos Economic Forum ?to reassure the world that the Russian economy was in good hands and that potential investors and their money should feel safe in Russia.?2 An economic counterintelligence directorate was created within the FSB?s Counterintelligence Department. On May 22, 1997, the FSB was once again completely reorganized. Its 14 directorates were replaced by 5 departments and 6 directorates, and the number of First Deputy and Deputy Directors was changed. All vacant posts were abolished, and a number of generals were forced into retirement; the FSB lost yet more qualified personnel, either to the MVD or the courts; some remained on a part-time basis, moonlighting on the side. Salaries were at an all-time low: Bennett cites figures of $370 a month for a Colonel with 15 years seniority, and $250 a month for a Lieutenant; SVR salaries were 50% higher, those of the FSO 150%.3 One solution to a number of these problems, which also allowed the FSB to legally infiltrate private business, was the creation of the prikomandirovannye sotrudniki (?staff on assignment?).4 The federal law on the FSB (article 15) states that ?in order to carry out security tasks, the military personnel of the organs of the FSB, while remaining in service, can be assigned to work at enterprises and organizations at the consent of their directors irrespective of their form of property.? This allowed thousands of FSB officers to be hired as ?legal consultants? in private companies and banks, where, using their connections and FSB resources, they provided krysha to their employer. Volkov cites data suggesting that up to 20% of FSB officials ?are engaged in informal ?roof? businesses as prikomandirovannye.? The ice cut both ways, as this extensive network useful furnished the FSB with information about private business. As Volkov notes, ?while it is possible to distinguish analytically between the search for a new job by former state security employees and their new operative assignments, an empirical distinction between the two phenomena has become virtually impossible.?

The FSB also sought to formalize its relationship with major businesses, as well as with the ChOPs and ChSBs providing security for them, by setting up a Consultative Council as a liaison and cooperation organ. The Council included both FSB officials and representatives of the major private security agencies emanating from the Soviet state security organs. Though the FSB announced that ?the council?s activity was to be based on state interest and its overall mission would be to assist the authorities in defense of society and individuals,? it in effect gave it an added institutional foothold in the krysha business, providing it with an effective channel of influence over some of the major violence-managing agencies. Most firms invited to join were eager to do so: ?In the general atmosphere of economic and political insecurity even the largest companies could not afford not to be represented on the Council. The Council had great potential to become a mix of security companies? semi-private club, a stock exchange of information and job centre.?5 The FSB could easily pressure those unwilling to cooperate by challenging or revoking vital licenses and permits. The Council though was potentially a double-edged weapon; as Bennett remarks, the FSB?s ?biggest problem was not that private companies would not want to cooperate but that the council would be used to get information from Lubyanka or that that the more talented and successful FSB officers would be head-hunted by private enterprise.? It did however prove a successful innovation, and was subsequently expanded, under Vladimir Putin, to formalize the ?coordination? between the FSB and the mass media, especially television.

The FSB was not the only agency tasked with work in the economic sector. On May 22, the same day the restructuration decree was promulgated, the ATTs?s Viktor Zorin was, officially, relieved of his duties; in reality, he was secretly transferred to head the Presidential Administration?s ultra-secret GUSP. The GUSP, as noted earlier, had been formed from the KGB?s 15. Directorate and was formally tasked with maintaining and exploiting the system of bunkers created to protect the country?s leadership in case of nuclear war, such as the huge complex built in the 1980s outside of Moscow.6 It is composed of two branches, the Service for Special Objects (i.e. bunkers) and an Exploitation-Technical Directorate, and controls a large force, the bulk of which are Army conscripts charged with maintenance and construction work. But in fact the GUSP?s powers have been expanded to make it an operational-analytical special service, a ?pocket? Presidential spetssluzhba tasked to deal with ?strategic problems linked to the political and economic interests of presidential power.?7 It was headed for many years by Vasily Frolov, who was fired in May 1998 for failing to anticipate and prevent the wave of strikes and protest actions engulfing Russia and embarrassing Yeltsin. The choice of a professional counterintelligence man and ?dirty-work? specialist to replace him was significant. Under Zorin, GUSP continued its operational work, dealing with the problem of capital flight to the West and hidden accounts; in 1998, after the crisis, it was instrumental in addressing the problem of the ?hard-currency corridor? out of Russia and helping the Central Bank stabilize the exchange rate of the ruble after its sudden collapse. But it also prepared programmes to solve regional, national and religious conflicts (given subsequent events, one might be tempted to speculate whether these ?solutions? did not include the kind of destabilization actions familiar to the ATTs). Finally, Mukhin, citing unattributed sources, states that Zorin, during his tenure at GUSP, prepared a special programme ?to neutralize the influence of the oligarchs,? whose stranglehold on the main assets of the Russian economy, media holdings, close relations to various power agencies, and political ambitions were proving more and more of a critical problem to the Presidency. Though Zorin was replaced, when Putin took power, by FSB Deputy Director Aleksandr Tsarenko, it is possible that the Kremlin?s massive, rapid and successful offensive in 2000 against both Gusinsky and Berezovsky, resulting in their departure from the country and dramatic loss of influence, drew on these earlier plans. (In 2004, it should be noted, GUSP was made into a federal agency, but Tsarenko remained in place and nothing was otherwise changed.)

The sudden collapse of the Barsukov-Korzhakov hegemony over the world of Russia?s special services left no single agency in a position of dominance. Over the next few years, rivalry between the different services intensified, or at least grew in visibility, often spilling over into the public domain. A number of ?hostile takeovers? of one agency by another were attempted between 1997 and 1999; though few succeeded, they clearly underline the bitter competition for influence and resources being played out. At the end of 1997, rumors began spreading about the resubordination of the FPS (the Border Guards) to the FSB. These rumors had a basis in fact: Yeltsin, told that the merger would save 10% of the FPS?s budget, signed an instruction in January 1998 ordering the government to prepare a draft decree, but later however rescinded it.8 In 1997 too the special SIZO ?Lefortovo? was returned to the FSB, boosting its executive capacity not only to investigate and arrest but once again to detain (in May 2005, Justice Minister Yuri Chaika announced that in order to fulfill Russia?s obligations to the Council of Europe, all FSB detention centers, including Lefortovo, would be transferred to the Justice Ministry). In September 1998, in order to bring Russia in line with its Council of Europe obligations, the GUIN was transferred from the MVD to ?civilian control? at the Ministry of Justice. As the transfer was effected right after the August financial crisis, and as the MVD furthermore refused to transfer the GUIN?s budget to the MinYust, the prison system found itself starved of funds, and the GUIN was obliged to appeal for international help to feed Russia?s more than a million prisoners; as part of this effort, GUIN granted access to numerous prisons to foreign journalists and aid officials, a first in the history of this closed system.

The battle for military counterintelligence also continued between the Armed Forces and the FSB; in 1998, at last, the FSB obtained full control over the osoby otdely, and military counterintelligence became a samostoyatelnyi directorate of the FSB under Col.-Gen. Aleksei Molyakov, regaining its old KGB number. Under Molyakov?s leadership, the 3. Directorate launched several controversial cases against journalists or environmental activists who had exposed corruption or ecological disasters in the Armed Forces; though the Russian constitution prohibits making ecological information a state secret, ambiguities in several laws allowed the FSB to imprison and prosecute a number of individuals for years. The best known-cases are those of Vladivostok military journalist Grigory Pasko, who was charged with treason in November 1997 after passing information to Japanese media about the embezzlement of Japanese grant money (for a nuclear waste processing plant) by senior Pacific Fleet officers; and of retired naval officer Aleksandr Nikitin, arrested and charged with espionage in November 1996 for passing information about the Russian Navy?s illegal dumping of radioactive waste material to a Norwegian environmentalist group.9

But the most vicious battle was the one fought over the future of FAPSI.10 FAPSI, since its creation at the end of 1993, had been one of the best-funded of the spetssluzhby, and had furthermore greatly profited from its control over key assets in the telecommunications business. In 1992 already, the KPS, as it was still called, had offered many former KGB senior officers rich opportunities for promotion and personal enrichment: whereas the KGB needed three directorates for its SigInt/ElInt work, the new structure had sixteen, and the number of generals rose from eighteen at the end of the Soviet era to seventy by the mid-1990s. For Yeltsin, it was the ideal spetssluzhba: able to collect information through its control of government communications and its intelligence means, yet relatively safe due to its lack of powers of investigation, arrest or detention; even its counterintelligence work had to be conducted by the FSB and other agencies. Over the years, FAPSI came to gain broad prerogatives in the fields of information and communications technologies, holding the right to deliver licenses in several key sectors. Thanks to Yeltsin, the agency gained a number of powerful tools in the first half of the decade. In September 1992 Yeltsin issued a directive setting up the Scientific Technical Centre of Legal Information ?Sistema,? partially financed by the State Property Committee, which ?was to co-ordinate work on information and telecommunication technologies, create a legal information system, updating the reference database of legal information and assure its accessibility for authorized users.? In June 1993, he created the Russian Governmental Information Network, which created on the basis of ?Sistema? a ?unified information-legal space covering the main organs of state authority of the Russian Federation.? In April 1995 he ordered a new Federal Centre for the Protection of Economic Information, to be supervised by FAPSI. The same month, worried about ?the growing power of several Russian companies and banks, the development of their security services and increasing telecommunication links between Russia and other countries,? he ordered the construction of a secure Special Purpose Federal Information and Telecommunications Systems (ITKS) for the state administrative agencies, with presidential status. The same decree ?made FAPSI the sole master of any coded communications in Russia and allowed it to inspect any commercial communications network.? In August 1995, finally, he ordered the creation of the GAS (State Automated System) ?Vybory? by FAPSI and the presidential Committee of Information Support Policy to transmit secure election results between every territorial electoral commission and the Central Electoral Commission. In April 1996 he ordered that a Russian Federation Situation Center, answering directly to the President, be set up and staffed by FAPSI. FAPSI, finally,

also runs the electronic communication links of both chambers of the Russian Parliament, and controls a data bank which consists of several integrated databases: economic, socio-political, legal, passport, special information, a sociological compendium of opinion polls, population, ecological problems, geographic/economic, business and market and emergency situations. The FAPSI information centre ?Kontur,? on the outskirts of Moscow, includes a database from 1,500 publications, statistical information and analysis concerning various aspects of the political situation in Russia. [?] FAPSI also runs the Regional Information Analysis Centres (RIATs) located in 58 regions of Russia. The centres analyze 1200 regional publications and send their analysis to Moscow. [?] The total number of information analysis centres was approaching three hundred by the end of 1999.

As Bennett comments:

This type of work would have been more appropriate for the FSB. By putting the centres under FAPSI?s supervision Yeltsin was trying to separate investigative bodies and those with powers of detention from information gathering and analytical structures. The regional leaders were less than enthusiastic about the new snoop centres. Not only were they Moscow?s information gathering outposts in the regions but the regions had to subsidize them as well.

The KPS, after the breakup of the USSR, inherited a number of key telecommunications assets that swiftly made it a major player in the market. It set up a number of commercial ventures, run by former officers still in the active reserve, to manage its extensive business activities. It controled the communications and money transfer systems of most major banks, and monitored all financial operations through its Federal Commercial Information Protection Center, set up in spring 1995 as a FAPSI directorate. As Bennett notes, ?in the increasingly privatized world of secure electronic communication in Russia FAPSI is the undisputed ruler.?11

Inevitably, senior officials with access to such means found it difficult to resist temptation. Beginning in the mid-1990s, after the FSB, responsible for FAPSI?s counterintelligence, launched several internal investigations of the agency, a number of senior FAPSI officers resigned, were fired or fled abroad. A major case finally brought the extent of corruption at FAPSI into the open:12 on April 12, 1996, the FSB arrested the head of FAPSI?s Financial-Economic Directorate, Maj.-Gen. Valeri Monastyrskiy, and accused him of embezzling at least 20 million DM and 3.3 billion rubles, mostly in connection with the purchase of equipment from Siemens. Monastyrskiy?s career is emblematic of the overlap between state security and business at FAPSI: a veteran KGB administrator, Monastyrskiy retired in 1992 to head three companies, Roskomtekh, Impex-Metal and Simaco, set up with FAPSI?s direct participation; in November 1993, he was hired by FAPSI while his wife took over Roskomtekh. The case soon made headlines, especially when the two rival services, locked in their power struggle, began leaking damaging information to the press. In March 1997, a year after his arrest, Monastyrskiy, still in prison, publicly claimed that he had been ?a victim of a conspiracy against FAPSI concocted by the head of the FSB General Barsukov, who wanted to merge FAPSI with his organization, and General Korzhakov, the head of the SBP, who wanted to share FAPSI?s budget.? FAPSI itself did not remain idle: ?The FAPSI collegium wrote to Boris Yeltsin complaining about the unprecedented attempt to discredit FAPSI leadership. Monastyrskiy?s lawyers conducted an aggressive campaign against their client?s detractors, aiming at specific personalities in the FSB. In revenge the FSB gave several journalists a list of FAPSI?s staggering corrupt practices and financial gerrymandering, with names, addresses and sums involved.? Detailed information about the illegal financial dealings of the head of FAPSI, General Aleksandr Starovoytov, and his family were thus published, though Starovoytov managed to retain his position until the end of 1998 (Monastyrskiy was released in September 1997 due to insufficient evidence). The change of personnel (Kovalev was also fired from FSB in July 1998) did not put an end to the struggle or the revelation of various kompromat. In December 1999 Vyacheslav Izmailov, the military correspondent of Novaya Gazeta, privately organized with several friends from RUBOP the arrest of an important Chechen kidnapper, Salavdi Abdurzakov. Abdurzakov owned the Chechen mobile phone company BiTel, which worked off FAPSI satellite assets, and was probably involved in the kidnapping and subsequent decapitation of four telecom engineers working for the British company Granger, who had come to Chechnya to help set up a company competing with BiTel. Izmailov, after turning Abdurzakov over to the authorities, gave the case much publicity, accusing FAPSI of keeping Abdurzakov in a safe house rather than in jail, and of trying to have him quietly released (due in part to Izmailov?s press barrage, Abdurzakov was finally sentenced to four years? imprisonment on reduced charges, but never served out his sentence).13 In May 2000 Novaya Gazeta, again, published information accusing the new head of FAPSI, Col.-Gen. Vladimir Matyukhin, and several of his subordinates of fraud, embezzlement and abuse of office; General Matyukhin in particular was accused of covering up the death of a conscript illegally employed in construction work at his dacha. The FSB, in spite of this barrage, failed to gain control of its rival?s prize assets (FAPSI was finally abolished in March 2003 but the FSB only got control of some of its directorates, the rest being shared out between the Ministry of Defense and the FSO). But this very public trading of accusations yielded precious information about the inner workings and corrupt deals of the spetssluzhby.

Aside from the economy, the second major challenge placed before the security organs was crime, and more specifically organized crime. We have already touched on the issue above, when discussing the development of the krysha business. The consolidation of crime groups, together with the increasing professionalization of their internal structures, methods of work, and provision of services had, within a year of the dissolution of the USSR, severely narrowed down the field; the vicious competition for ?customers? and territory exploded onto the streets of Moscow in 1993, with the start of the famous ?Mafia War? that caused hundreds of casualties over the next eighteen months. By 1994, the playing field had been cleared out, and only the major actors remained standing. Having to compete now with both the ChOPs and branches of state agencies in the krysha business, crime groups sought to diversify, investing where they could in legal businesses; they of course maintained their control over ?illegal? economic sectors, such as the drug trade, though even here they had to compete with corrupt, ?privatized? elements of the force structures. Attempts by some Russian crime groups to expand abroad met with mitigated success: in developed capitalist economies, there was no need for the elaborate gamut of services provided by krysha, and Western companies could count on functioning law enforcement organs to fight off cruder attempts at instituting protection rackets; as for other sectors of the criminal economy, the Russians, faced with murderous competition from long-entrenched groups (such as the Italian, Columbian, or Jamaican mafias in the US), found it difficult to carve out a sustainable niche and were in many places forced to retreat (though they are reported to control a substantial portion of Israel?s illegal sectors). In Russia, however, krysha was now a key structural element of the developing capitalist economy, the oil that greased all the wheels, the crucial mechanism that rendered commerce possible. In 1998, the string of defaults touched off by the August financial crisis triggered a violent response from kryshy seeking to recover their clients? debts: over the following year, murders of bankers and CFOs became a weekly occurrence.

While at the micro level various branches of state organs competed with the crime groups, legally or not, for a share of the krysha market, at the macro level the authorities had few tools at their disposal to grapple with the problem of organized crime. Though FSB also had an organized crime unit, the MVD remained the principal state actor tasked with fighting crime. But under the ministership of Anatoly Kulikov, the struggle against organized crime was not a major priority at MVD. Col.-Gen. Kulikov was a career VV man who had come up through the ranks; as commanding officer of the VV troops in the SKVO (North Caucasus Military District) in 1990-92, he had been involved in the Ossete-Ingush conflict (during which Russian forces openly supported the Ossete militias chasing ethnic Ingush from Prigorodnie District), and had witnessed with horror Dudaev?s rise to power and declaration of independence. In 1992 he was promoted to Commander of the VV and Deputy Interior Minister; he played a leading role in the storming of the White House in October 1993. In January 1995 he accepted the position of Commander-in-Chief of the Joint Federal Forces (OGFS) in Chechnya, a position several Army Generals, including Col.-Gen. Eduard Vorobyev, had turned down. Units under his command perpetrated a number of atrocities in Chechnya, the best documented being the massacre by Interior Troops of over 200 unarmed civilians in the village of Samashki on April 7-8, 1995. In July 1995, Kulikov was named Interior Minister in place of Viktor Yerin, who had resigned in the wake of the Budennovsk tragedy. MVD bodies under his responsibility, both the VV and the GUIN (which ran parts of the ?filtration camp? system, where prisoners were routinely tortured and murdered), continued to commit war crimes in Chechnya, with little oversight from the ministry. In March 1996 Kulikov reportedly played a significant role in talking Boris Yeltsin out of a plan, apparently prepared by Korzhakov and Barsukov, to cancel the upcoming presidential elections and ban the Communist party. After the Khassav-Yurt peace accords, which he opposed, Kulikov came into public conflict with Aleksandr Lebed; Yeltsin, for whom Lebed had outlived his usefulness, sided with Kulikov and unceremoniously sacked Lebed.

With the appointment of Kulikov, the rest of the ministry was rapidly militarized. The aims of this reform were to make it capable of protecting the political leadership more effectively, improving their capabilities as a combat force able to fight well organized and well armed groups in the Russian Federation and purging corrupt officers, NCOs and contract soldiers. The losers were the crime fighting elements of the ministry. The top militia officers were not invited to some of the Ministerial meetings and only the voices of discontent from the SBP stopped Kulikov from militarizing the Russian traffic police.14

Building up the VV, whose overall performance in Chechnya had proved appalling, into an effective fighting force and rooting out corruption within the Ministry were thus Kulikov?s two priorities during his tenure. Kulikov has repeatedly discussed how he discovered with shock the extent of corruption within MVD upon being made Minister; but in his well-publicized battle against the phenomenon he proved as unsuccessful as every reformer that had come before him. Shortly after his appointment, he launched a massive ?clean hands? operation; yet though a number of officers and even senior officials were dismissed, this had little impact on the ordinary police?s deeply ingrained practices. Kulikov also attempted a number of publicity stunts, personally going undercover as an ordinary driver on various roads to catch bribe-takers, or sending a truck loaded with vodka up from Vladikavkaz to Rostov and secretly videotaping the inspection proceedings: only two out of twenty-four traffic policemen refused the bribes offered, and Kulikov had over 30 officials fired.15 His obsession with this problem brought him into conflict with Vladimir Rushaïlo, then head of the Moscow RUBOP which he had built up since 1990; Kulikov launched 38 investigations into RUBOP?s business activities, but failed to corner Rushaïlo, who was closely allied to Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov as well as to Aleksandr Lebed and the oligarch Boris Berezovsky. In October 1996, finally, in a bid to remove Rushaïlo from RUBOP, Kulikov offered him the position of First Deputy Head of GUBOP; Rushaïlo refused and left MVD altogether, taking up a position as legal advisor to the Chairman of the Federation Council, Yegor Stroyev.

As for the VV, it was indeed in poor shape. During the first Chechen conflict it had proved even more underfunded and combat-ready than the Army, and Kulikov fought strongly for increased budgets. His attempts to expand the VV?s size and combat power, especially in the SKVO, led however to open accusations from Duma deputies (as well as from Aleksandr Lebed) that Kulikov was seeking to form a private army. Kulikov defended his proposals, arguing ?that the problems associated with internal unrest were the primary threat to the unity of Russia and demanded such increases.?16 At the same time, unusually for a VV man, Kulikov maintained good relations with the Armed Forces, even appointing an Army General, Leonti Shevtsov, to replace him as head of the VV. Kulikov, always a hard-liner when it came to ethnic conflicts within Russia, seems to have believed that the peace agreement signed with Aslan Maskhadov in August 1996 would never last, and his actions in building up the VV?s combat power strongly resembled, to many observers, preparations for renewed conflict in Chechnya. When Khattab?s forces attacked an MVD base in Buinaksk in December 1997, Kulikov reacted strongly, declaring that ?...we have a right to make preventive strikes against bandit bases, wherever they are located, including the territory of the Chechen Republic. This is my view, and I intend to inform the President of this.?17 But open conflict with Chechnya was not on the agenda and both the Chechen authorities and leading Russian politicians sharply criticized Kulikov?s statements, forcing the minister to back down. As Thomas writes, Kulikov ?appeared to disagree fundamentally with President Yeltsin in two areas: the government's policy in the North Caucasus, which Kulikov viewed as too soft; and the government's policy toward military reform, which Kulikov viewed as impossible to execute without an increase in the armed forces' budget.?18 Two months after Kulikov?s statement on Buinaksk, Yeltsin dismissed Prime Minister Chernomyrdin and his government; Kulikov ? who learned of his own dismissal from the media ? was the only minister not reconfirmed.

In place of Kulikov Yeltsin named his favorite silovik, Sergei Stepashin. Stepashin brought his reformist zeal to the ministry, rapidly reversing Kulikov?s militarization and recentering the MVD?s activities on crime-fighting. He eliminated the MVD?s Main Staff, and replaced it with a Main Organizational-Inspection Directorate; he also reduced the overall troop levels of the VV, and cut the number of MVD military districts from seven to four. At the same time, he did not neglect the North Caucasus, though his approach was markedly different from Kulikov?s. Yeltsin?s March 1998 purge had also brought down the Secretary of the Security Council, Ivan Rybkin, a Berezovsky ally who had become the Russian Government?s point man on Chechnya. Following his and Berezovsky?s departure from the Security Council, Stepashin took over the Chechnya dossier. He met on several occasions with Turpal-Ali Atgeriev, Maskhadov?s Minister for State Sharia Security, and adopted a conciliatory discourse with him, though he failed to provide Maskhadov with the assistance he sought to curb the rising power of islamic extremists and criminal groups in the Chechen Republic. When the authorities of Daghestan, in the fall of 1998, came into conflict with local ?Wahhabi? villages whose inhabitants, though they otherwise remained peaceful, had chased out corrupt police officials and imposed sharia, Stepashin acted as a mediator, granting the villages an unprecedented form of legal autonomy. Yet Stepashin did not neglect the military element: throughout 1998, the MVD took the lead within SKVO, setting up joint military exercises with the FSB and the Armed Forces aimed at improving inter-service coordination and capability in case of renewed conflict. At the same time, in July 1998, and perhaps at Stepashin?s instigation, Yeltsin redefined seven voyennye okruga (military districts) for the entire country and ordered all other executive security bodies, especially the VV, to bring their unit borders into line so as to avoid overlaps in command & control.

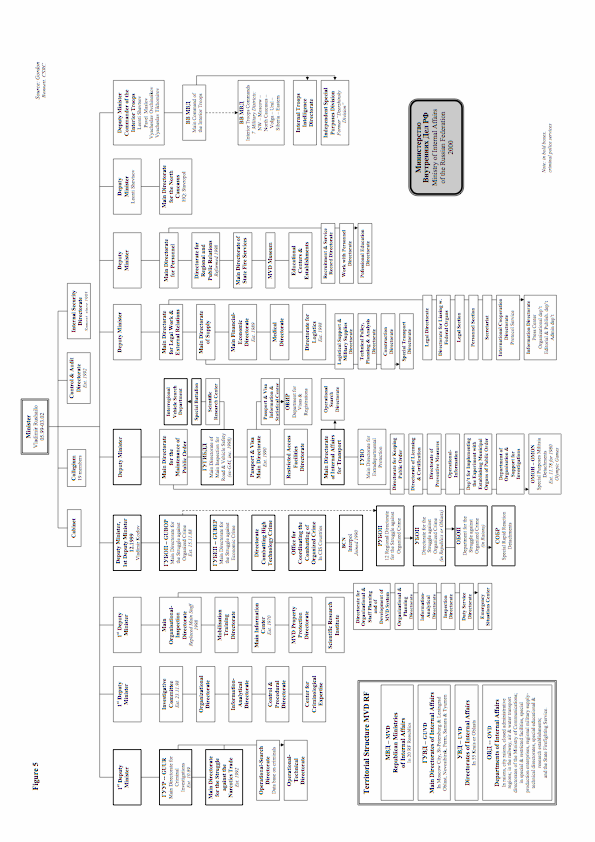

By the time Stepashin was named Prime Minister, on April 27, 1999, his attempts at reforming and improving the MVD?s performance had brought as few concrete results as Kulikov?s. One of Stepashin?s main plans had centered around uniting the so-called ?criminal block,? GUUR, GUBOP and GUBEP, into a Criminal Police Service under direct Federal control, while delegating public order and traffic police to the regions, which would finance these services directly; the reform however was bitterly opposed both by the Ministry?s central staff and by the still-powerful governors, and was quietly dropped (Interior Minister Boris Gryzlov tabled the plan again a few years later, but it has yet to be implemented). He had also spearheaded the creation, in November 1998, of an Investigative Committee, ?an internal watchdog ... empowered to conduct preliminary investigations within the ministry to make sure that it acts in accordance with its own rules and regulations.?19 The anti-corruption campaigns ritually announced by each of Stepashin?s successors suggest that this body has had as little success as its predecessors in policing the police. Stepashin was replaced as Interior Minister by the RUBOP veteran Rushaïlo, who had returned to MVD in May 1998 as First Deputy Minister in charge of GUBOP (then still GUOP), and who had profited from his time at the Federation Council to build close links to the all-powerful ?Family? clique surrounding the ailing Yeltsin. Rushaïlo, considered by most observers a ?Berezovsky? man, took an active part in the raging intrigues of the last years of the Yeltsin regime, and pursued his previous corrupt practices on an even broader scale. Fig. 5, above, gives the broad organizational outline of Rushaïlo?s MVD.20

In Chechnya and throughout the North Caucasus, the kidnapping epidemic had grown beyond all control. It had begun immediately after the end of the war; most of its victims were Chechens, Russians, or members of neighboring ethnic groups, but foreigners were also systematically targeted. By 1997, virtually all the humanitarian organizations still working in the region had pulled out, and journalists only rarely ventured into the Republic, contributing to the ?information blockade? sought by Moscow. A number of high-profile cases, such as the kidnapping of several NTV and ORT correspondents and of Yeltsin envoy to Chechnya Valentin Vlasov, had yielded multi-million dollar ransoms for the groups holding them. Boris Berezovsky, as Deputy Secretary of the Security Council, played a highly visible role in freeing hostages, often greeting them in front of television cameras as they returned to Moscow. His adversaries and critics accused him of using the kidnappings as a pretext to channel large sums of Russian government money to various Chechen extremists; and indeed Berezovsky, and his right-hand man Badri Patarkatsishvili, preferred to work with the most radical elements in Chechnya such as Shamil Basaev and Movladi Udugov, while shunning Maskhadov and his anti-terror and anti-kidnapping chiefs, Khunkar-Pasha Israpilov and Shadid Bargishev.21 Other visible players in solving kidnappings included Stepashin and the ATTs?s Viktor Zorin, whose ambiguous role has already been discussed. Rushaïlo, when he returned to the MVD, also got involved, working through his GUBOP or its North Caucasus branch, the Nalchik RUBOP headed by General Ruslan Yeshugaev. In one case that received some publicity in the press, Rushaïlo was said to have personally waited in a house near the Ingush-Chechen border while his forces conducted an operation to free the French UNHCR official Vincent Cochetel, an operation during which several kidnappers were killed. French media however reported that the French government had given Rushaïlo a sum in excess of $3 million for the negotiated liberation of Cochetel; informed sources believe Rushaïlo double-crossed both the French and the kidnappers, putting the hostage?s life at risk by ordering a forceful liberation while keeping the money for himself.22

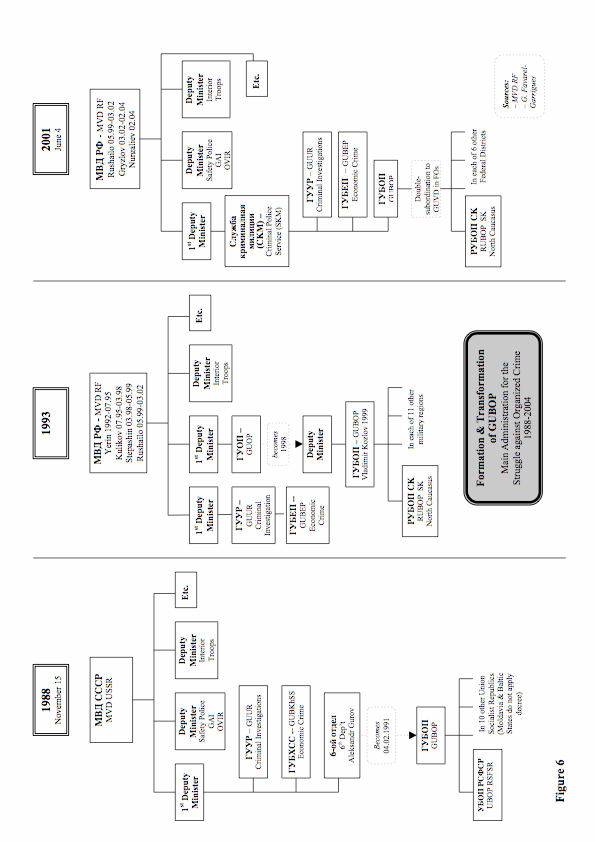

GUBOP, Rushaïlo?s ?favorite toy,? reached the peak of its powers under his leadership (see Fig. 6 above). Gurov?s 6-oï otdel had first been renamed GUBOP in February 1991, and UBOPs were ordered established in every Union Republic (Moldavia, already embroiled in civil war, and the three Baltic States, which were no longer paying much attention to Moscow?s decrees, failed to comply). One of GUBOP/GUOP?s subsequent major innovations was the introduction, in 1993, of an intermediary, regional level of its organized crime-fighting structure. Gurov, during the Soviet period already, had long argued that the close links and even corrupt collusions between Republican MVD chiefs and local Communist party bosses made it nearly impossible to fight organized crime at the local level; in line with this logic, the MVD now created twelve RUBOPs, structures to which the oblast UBOPs reported directly (rather than to the oblast UVD); RUBOP, in turn, reported to GUBOP in Moscow. This regional structure remained a particularity of the GUBOP system throughout the 1990s; only after Vladimir Putin created the Federal okrugs in 2000 was it slowly extended to other MVD branches such as the criminal police (GUUR) or the GUBEP system. In 1992 GUBOP, renamed GUOP, became samostoyatelnyi within the MVD, under the direct control of a First Deputy Interior Minister, the position Rushaïlo obtained in May 1998. Upon becoming minister, Rushaïlo downgraded the rank of GUBOP?s new boss, Vladimir Kozlov, to Deputy Minister, but left the structure samostoyatelnyi; in December 1999, he once again made Kozlov a First Deputy Minister. During this period, 1998-2000, GUBOP and the Moscow RUBOP had become, in the words of one well-placed observer, ?the Kings of Moscow,?23 taking over the SBP?s former highly visible position as the prime suppliers of protection and influence for businesses and individuals. The distinctive style of GUBOP officers ? short haircuts, leather jackets and blue jeans ? deliberately mimicked the appearance of the criminals they were supposed to fight. Their influence extended widely. ?Almost from the start,? writes Donald Jensen of the Moscow RUBOP in his study of the ?Luzhkov system,?

RUBOP was not a fully budget-funded organization. Rather, it received funds from interested private firms and individuals, as well as public money. [?] In its diverse business interests and effectiveness in providing a krysha for some of the city's major businesses, as well as its ties to federal and city authorities, RUBOP resembled an organized crime group itself.24

After Rushaïlo was dismissed and replaced as minister by Putin loyalist Boris Gryzlov, there was much talk of dissolving GUBOP altogether, and attempts were apparently made to do so; yet GUBOP survived, albeit reduced in status and resubordinated to the regular crime-fighting hierarchy (Kozlov was superannuated from MVD in December 2002, and promptly landed on his feet as Deputy CEO of a major firm, ?Severstal?).

By 1998, the ?sacred alliance? of the major oligarchs, formed in 1996 in the face of a potential Communist comeback, had utterly collapsed, and as the end of Yeltsin?s reign slowly approached the fight over his succession began to heat up. Whereas, in terms of public notoriety, Yeltsin?s first term had been dominated by Most?s Vladimir Gusinsky, the key player of his second term was undoubtedly Boris Berezovsky. His term as Deputy Secretary of the Security Council, under Rybkin, did not last more than a year, and he was fired at Chubais?s instigation; but he had meanwhile successfully built up his relationship with Yeltsin?s closest entourage, the so-called ?Family? ? Yeltsin?s daughter Tatyana Dachenko, his ghostwriter and Head of Presidential Administration Valentin Yumashev, and the future and highly influential Head of P.A., Aleksandr Voloshin ? a tight-knit group of which he rapidly became one of the lead figures. Berezovsky of course had been seeking to gain influence over the various security organs; by 1998, he could fully count on the support of the Moscow RUBOP and of MUR (the Moscow Criminal Police department), and he had grown powerful enough to play a leading role in the downfall of Kulikov, who not only had opposed his protégé Rushaïlo, but was also fronting for the Chierny brothers, powerful Siberian mafiosi who were Berezovsky?s bitter rivals in the ongoing conflict for the control of Russia?s aluminium production. But Berezovsky also had powerful enemies at FSB, whose director Kovalev refused to cooperate with him. At the start of 1998, Berezovsky went after Kovalev and the FSB. On March 27 he requested a meeting and informed Kovalev that members of a top-secret FSB department, URPO, were seeking to assassinate him.25 URPO (the Directorate for the Analysis & Suppression of Activities of Criminal Organizations) was the successor department to the UPP, the Long-Term Programmes Directorate created after the first Chechen war under the direction of Colonel Yevgeny Khokholkov, the man who according to Aleksandr Litvinenko directed the assassination of Dzhokhar Dudaev. The UPP, replaced by URPO in 1997 (Khokholkov was promoted to Major-General), commanded substantial technical means, including its own transport, premises, and surveillance equipment, and controlled various ?private? security firms. Officially, it had been established by Yeltsin to fight organized crime; Litvinenko however claims that its main tasks were to carry out ?wetwork? for the FSB, including contract hits: ?[URPO] was established in order to identify and neutralize (liquidate) sources of information representing a threat to state security.?26 Indeed most of the information concerning URPO comes from Litvinenko; given however his proximity to Berezovsky and his deep implication in the dissolution of URPO and the fall of Kovalev, it is difficult to assess his reliability as a source. Berezovsky, at his March 1998 meeting with Kovalev, said he had learned of the murder plot from Litvinenko, who served at that time as a Lieutenant-Colonel within URPO; Litvinenko and his colleagues, ordered to kill Berezovsky by Khokholkov and his deputy Aleksandr Kamyshnikov, refused and informed first Yevgeny Savostyanov ? at this time Deputy Head of Presidential Administration in charge of the special services ? and then Berezovsky himself. It should be noted however that Litvinenko had previously worked closely with MUR, a Berezovsky bastion, knew Berezovsky personally, and had on occasion moonlighted for him. Kovalev suspended the suspects and ordered an investigation; in May, the investigators concluded that the charges were groundless, and Khokholkov and Kamyshnikov were reinstated. A few months later, however, Kovalev, weakened by Berezovsky?s intrigues and his conflict with FAPSI, was dismissed. Berezovsky meanwhile had returned to the government as Executive Secretary of the CIS. In November, he repeated the accusations against URPO in an open letter to the new Director of the FSB, Vladimir Putin; on November 23, he organized a press conference on ORT, a TV channel he controlled, during which Litvinenko and his colleagues, openly giving their names and ranks, told the story of the murder plot against Berezovsky and further accused URPO of seeking to kidnap Khusein Dzhabrailov, the brother of the notorious Moscow-based Chechen businessman Umar Dzhabrailov. The officers stated that Kovalev had full knowledge of the planned operations. URPO was then disbanded and Khokholkov was fired; Litvinenko and his colleagues were also sacked, finding jobs on Berezovsky?s staff at the CIS. (Litvinenko was subsequently arrested on unrelated charges, in spring 1999, and was exfiltrated from Russia, along with his family, with Berezovsky?s assistance. He now lives in the U.K., where he was granted political asylum, and remains very close to Berezovsky.)

Shortly before Kovalev?s dismissal, the FSB was once again restructured (see Fig. 4, above); it is possible that Stepashin, now Interior Minister, had some influence over these reforms as well as those undertaken under Putin a mere six weeks later. In line with the priority given to the economy, the Economic Counterintelligence Directorate was taken out of the Counterintelligence Department and made a samostoyatelnyi department, the DEB or Department for Economic Security. The military counterintelligence directorate, as already explained, was also made into a separate and more powerful unit. The Counterintelligence Department now included a Counterintelligence Operations Directorate as well as an Information & Computer Security Directorate. Russia indeed was beginning to pay more attention to the question of information security; in 1998, the FSB was given the legal right to force internet provider companies to install interception equipment on their servers, a system named SORM (System for Operational Intelligence Measures).

?I have come home,? Vladimir Putin declared before the FSB Collegium when introduced by Prime Minister Kiriyenko, in July 1998, as their new Director. With his nomination, a new chapter in the history of the Russian security organs was about to open; yet the beginnings were not auspicious. Putin, unlike his predecessor, could not be considered a high-level security professional; during his KGB career, he had only reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and he had left the KGB when the USSR broke up to go work for the Mayor of St.-Petersburg, Anatoli Sobchak, as his Deputy for External Economic Affairs. In this position, where he surrounded himself with former Leningrad KGB colleagues, Putin made many influential relations; there are also persistent allegations that he profited financially from his position, which would hardly have been unusual. When Sobchak lost his re-election bid in 1996, Putin stood by him, organizing his flight from Russia before he could be indicted by his successor on various charges of corruption and abuse of office. This show of loyalty apparently impressed people in Moscow, including Chubais, at this stage Head of the Presidential Administration; Putin, backed by Aleksei Kudrin (now his Finance Minister), was invited to come work in the Kremlin. There, he was given a position in the Kremlin Property Department under Pavel Borodin, another powerful member of the ?Family? who would later be indicted in Switzerland on corruption charges. In 1997 Putin was made Head of the Presidential Administration?s Main Control Directorate (GKU), a powerful oversight body described as ?a mini-KGB under the head of the government.?27 In June 1998 he was briefly named Deputy Head of Presidential Administration for relations with the regions, a position in which he first came into direct contact with the caste of powerful regional barons who allowed the Kremlin little say in the affairs of their fiefs; this experience certainly fueled his insistence on aggressively imposing a ?vertical of power? on the regional governors as soon as he came to power. A mere six weeks after taking up this position, however, he was moved over to the FSB. Two weeks later, Russia was hit by the financial crisis and its economy abruptly teetered to the brink of collapse. As turmoil rocked the government, Yeltsin continued restructuring the FSB (see Fig. 4 above): on August 26, the leadership was reorganized, with the FSB Director being given a second First Deputy, a State Secretary, and an additional Deputy; the Collegium was increased to seventeen members, whose nomination had to be approved by the President. The new State Secretary position was abolished in another reform on October 6, but the rank of the head of the St.-Petersburg UFSB was upgraded to Deputy Director (the position had been held since 1992 by Putin?s close ally Lt.-Gen. Viktor Cherkesov, who had succeeded Stepashin). That same month Putin brought another old ally back into the FSB: Nikolai Patrushev, who had replaced him as head of the GKU but had been dismissed after initiating a case against the arms-trading firm Rosvooruzheniya; Patrushev was made head of the DEB, with a rank of Deputy Director. Putin created a Department for the Security of Nuclear Facilities in October; in November, the Information & Computer Security Directorate was separated out from the Counterintelligence Department. As Director of FSB, Putin reportedly proved highly unpopular; the generals under his command resented being given orders by a former subordinate officer whom they considered an upstart political appointee, and subtly resisted his authority. The flight of cadres resumed, fed by the economic difficulties the FSB, like every government agency, suffered in the wake of the crisis. Putin, meanwhile, kept his eye firmly on the political ball, cultivating his relationship with Boris Yeltsin and securing, in March 1999, his nomination as Secretary of the powerful Security Council, while retaining his FSB post.

To replace the powerful Chernomyrdin, in March 1998, Yeltsin had chosen a relatively unknown young liberal economist, Sergei Kiriyenko. Berezovsky, through his media organs, did everything he could to oppose his confirmation in the Duma; as Fuel & Energy Minister, Kiriyenko had opposed Berezovsky?s attempts to rig the privatization of Rosneft, and he was close to Chubais, Berezovsky?s arch-enemy.29 Kiriyenko finally squeaked through the Duma, but, facing intense opposition on all sides, was unable to remedy Russia?s disastrous economic state; the August 17 financial crisis cost him his position after only five months on the job. Yeltsin, in his place, attempted to nominate Chernomyrdin again, but found himself blocked by an incensed Communist-dominated Duma. Finally, to avoid a constitutional crisis, Yeltsin dropped Chernomyrdin and nominated his Foreign Minister Yevgeny Primakov for the post. Primakov, a conservative, patriotic official with good ties to the Communists and a reputation for personal honesty, was immediately ratified by the Duma. As the former head of the SVR, he inaugurated the reign of the siloviki that dominated Yeltsin?s last years. Primakov however soon began steering his own course, one that looked increasingly dangerous for Yeltsin and his cronies. In the fall of 1998, the Duma began to initiate impeachment proceedings against Yeltsin. Primakov attempted to broker a deal in which the proceedings would be dropped and Yeltsin and his family would be guaranteed immunity after the end of his term; in return, Yeltsin would not change the composition of the government without the consent of the Duma: Yeltsin, pushed by his close advisors, refused. In December, in yet another attempt to shore up his weakening position, Yeltsin initiated a massive purge from his hospital bed, firing, among others, his Head of Presidential Administration, Valentin Yumashev, the P.A.?s Deputy in charge of the special services, Yevgeny Savostyanov, and the Director of FAPSI, Aleksandr Starovoytov. None of this did him much good, and his position was looking increasingly precarious: if the highly popular Primakov replaced him, as looked quite probable at that time, neither he nor his family would be safe from prosecution. His formerly loyal General Procurator, Yuri Skuratov, had already escaped his control. In February 1999, Skuratov, with Primakov?s authorization, launched a legal assault against Berezovsky?s empire as well as against several of his close allies, especially the banker Aleksandr Smolensky and the aluminium magnate Anatoly Bykov.30 Anatoly Chubais also found himself under investigation; and since December 1997 Skuratov had been assisting a Swiss investigation into Kremlin corruption that involved Pavel Borodin, Putin?s mentor at the Presidential Administration. His investigations were now directly targeting members of the ?Family.? At this point the new Head of the P.A. and Secretary of the Security Council, Nikolai Bordyuzha, showed Skuratov a videotape in which a man resembling him was seen frolicking with two prostitutes. Skuratov tendered his resignation, but the Federation Council refused to accept it and he rescinded it. In March, after a discussion with Primakov and Skuratov, Yeltsin fired Bordyuzha, replacing him with Voloshin at the P.A. and Putin at the Security Council. But Yeltsin was also forced to dismiss the embattled Berezovsky on April 2 from his position as executive Secretary of the CIS; four days later, with Berezovsky already abroad, Skuratov issued a warrant for his arrest. The tape was then leaked and shown on television; on April 9, Stepashin and Putin held a joint televised press conference in which they discussed the case. As the Russian political analyst Andrei Piontkovsky describes the scene,

I think the family around Yeltsin started thinking of Putin as the successor after the famous press conference with Putin and Stepashin. They had a chance to compare the two of them in this circumstance. Stepashin was Interior Minister and Putin was the FSB Director and you could see their behavior. It was necessary to prove the authenticity of the tapes showing Skuratov with the prostitutes. Stepashin was looking down at the floor blushing. Putin was calm and resolute as always. Putin reported confidently that ?we have conducted expert analysis of genitalia ? measurements and so forth and indeed this is Skuratov.? [Piontkovsky is being ironic in his choice of words, but Putin did indeed state that expert FSB analysis proved the man on the tape was Skuratov.] This was a very serious test. After this, the family could see that this one would go to any lengths. His readiness to serve in the Skuratov case made him a very serious candidate.31

Skuratov was finally removed, and his replacement, Vladimir Ustinov, promptly launched a criminal investigation against him. Berezovsky, in Paris, was rescued by Interior Minister Stepashin, who declared that if he returned to Russia to talk with prosecutors he would not be arrested. Stepashin kept his word; and upon his return Berezovsky unleashed a full-scale assault against Primakov, who was sacked by Yeltsin less than a month later, on May 12. ?The dismissal of Primakov was my personal victory,? gloated Berezovsky.32 The impeachment drive fell through three days later. But in spite of Berezovsky?s support for his protégé Deputy Prime Minister Nikolai Aksyonenko, the man chosen to replace Primakov was Chubais?s choice, Yeltsin?s most loyal silovik, Sergei Stepashin.

Analysts still disagree as to whether Stepashin was only given the job to keep the seat warm until the plan for Yeltsin?s succession was ripe, or whether he was indeed, in the spring of 1999, being groomed as a potential successor himself. A comparison of Stepashin and Putin?s career clearly shows that while in the early 1990s Putin was a far more minor official than Stepashin, he rapidly began to catch up, and by 1998, when he was named to the FSB, he appears always just a step behind Stepashin, dogging his heels. It is possible that from a certain point onwards Putin was deliberately groomed as a potential fall-back candidate in case the Stepashin option didn?t play out; Lanskoy argues that he owed most of his major promotions to Berezovsky,33 which if true would reinforce this interpretation. Stepashin himself later made hints in this direction, claiming he had been dismissed as Prime Minister in August 1999 in part ?because he could not be bought.?34 This of course is not the whole truth: the initial plan to launch hostilities against Chechnya, which played such a significant role in Putin?s accession to power, had been drawn up by Stepashin in March 1999. But we will see that when it indeed came to full implementation of the plan Stepashin wavered; and Putin did not, and got the prize for his pains.

The events of the summer and fall of 1999, which brought Putin to power, remain shrouded in mystery; a great many allegations have been made concerning them, but the lack of any independent investigation make it impossible to prove or disprove the theories. The bare facts are as follows. On August 4, Daghestani islamic radicals led by Bagaudin Kebedov, who had recently returned from Chechnya to the mountainous district of Tsumada in Daghestan, clashed with MVD policemen, killing four. Stepashin flew to Makhachkala on August 6; the next day, over a thousand heavily armed fighters, mostly Daghestani but led by the famous Chechen field commander Shamil Basaev and his deputy, the Saudi mujahedeen known as Khattab, crossed over into Daghestan. Basaev declared that he intended to unite Chechnya and Daghestan into an Islamic Caliphate; heavy fighting immediately broke out with Daghestani and Federal forces. On August 8, Stepashin returned to Moscow and was dismissed; Yeltsin immediately named Putin in his place, presenting the little-known FSB Director to an astonished public as his choice as successor. The new Prime Minister vowed to crush the rebels within two weeks; major combat operations followed, during which command of the operation, as the Federal Forces suffered heavy casualties, was handed back and forth between the Armed Forces and the MVD. Putin loyalist Nikolai Patrushev was named to replace him at the head of the FSB. On August 23, after bitter fighting during which several villages were destroyed, Basaev and his forces withdrew to Chechnya; numerous eyewitnesses say that the Federal Forces did nothing to impede his retreat. On August 27, Putin flew to Makhachkala and ordered a punitive attack against the Wahhabi villages of the Kadar zone (to which Stepashin had granted limited autonomy a year earlier) even though they had not participated in the uprising. On the night of September 4, as the Federals were struggling to wipe out the last bastions of resistance in the Kadar villages, a car bomb destroyed a military housing building in Buinaksk, killing 64 people, mostly wives and children of officers. That same morning Basaev and Khattab launched a renewed incursion into the lowland Novolak region of Daghestan, coming within a mere five kilometers of the regional capital Khassav-Yurt and threatening Makhachkala. Federal Forces supported by local volunteers, including Akkhin Chechens from Daghestan, finally forced them back after more brutal fighting; meanwhile, the Russian Air Force had already begun bombing ?rebel bases? inside Chechnya as well as villages close to the border with Daghestan.

On September 9, in the middle of the night, a massive bomb completely destroyed a building on Moscow?s working-class Guryanova ulitsa, killing 94; a second explosion on the 13th, on Kashirskoe shossee, killed 119; on the 16th, a bomb targeted a building in the city of Volgodonsk, killing 17. As the country stood in shock before this unprecendent wave of terrorism, Prime Minister Putin blamed Chechnya ? whose President Maskhadov had immediately denounced Basaev?s incursions into Daghestan ? for harboring terrorists and vowed to pursue them anywhere, declaring, in a phrase now famous, that he would even ?ikh zamochit? v sortire,? ?waste them in the shithouse.? His firm demeanor combined with his use of crude criminal slang drove his popularity ratings (which hovered around 2% when he was nominated) through the ceiling and propelled him to the forefront of Russia?s political class. The failed bombing of a building in Ryazan on September 22 openly exposed the FSB?s involvement; when FSB Director Patrushev announced that it had in fact been an exercise (half an hour after Interior Minister Rushaïlo stated it was a failed terrorist act), few believed the excuse; a week after the incident, Aleksandr Lebed, answering a Le Figaro journalist who asked him if he thought the government had organized the terrorist attacks, created a sensation by saying out loud what many were thinking: ?I am almost convinced of it.? (Berezovsky promptly flew to Krasnoyarsk, where Lebed was now governor, to talk to him; no one knows what was said, but Lebed never repeated his allegations.)35 None of this however did anything to derail Putin?s rise. On September 23, he ordered the bombing of Groznyi, killing numerous civilians; Maskhadov?s frantic attempts to initiate a dialogue with Moscow or neighboring governors were openly blocked by the Kremlin. At the start of October, the Federal Forces, having amassed a joint body of over 100,000 Armed Forces and MVD troops, crossed into Chechnya.36 It seems that the initial objectives had followed the March ?Stepashin Plan,? which Stepashin himself publicly discussed the following year:37 the Federals were to bomb the main Wahhabi training camps in Serzhen-Yurt and Urus-Martan and advance up to the North bank of the Terek to create an impregnable cordon sanitaire around the wayward Republic; negotiations would then be initiated from this position of force. But Putin had already decided to go further. The decision to fully invade Chechnya was reportedly taken in Mozdok on September 20, at a meeting with the Chief of the General Staff, General Anatoly Kvashnin, called to iron out the parameters of the partnership between the new Prime Minister and the Armed Forces. Kvashnin was the leader of a group of generals who had made their careers thanks to the first Chechen war, and who had been profoundly humiliated by the August 1996 ?surrender;? at the meeting, apparently, the Army brass rejected the limited Stepashin plan and offered to back Putin fully if they were given a free hand in Chechnya: Putin accepted, cutting a deal that would come back to haunt him over the following years.38

Most of the theories put forth suggesting that the Daghestan incursions and the Moscow bombing campaign were part of a deliberate plan to start a war with Chechnya so as to build up Putin?s image and insure his election place Berezovsky squarely at the center of the plot.39 The evidence, mostly circumstantial, is too detailed to go into here, and the interested reader is referred to the extensive literature on the subject.40 For Daghestan, most of the evidence rests on Berezovsky?s known links to the Chechen islamic radicals, several transcripts of phone conversation between him and the radical leader Movladi Udugov, leaked to the Russian press in September 1999, and the extensive eyewitness evidence that Russian troops guarding the border with Chechnya were ordered back before the incursion, were on several occasions forbidden from engaging the rebels, and provided them with a ?corridor? back out of Daghestan (initial Federal bombings of Groznyi, while targeting a market and other civilian areas, mysteriously spared both Basaev and Khattab?s command posts, whose locations were well known to Russian intelligence). There are also numerous reports, partly substantiated by Berezovsky himself, that he paid several million dollars to Basaev; reports in the Russian media of a July 1999 meeting in Nice involving Basaev, his former GRU kurator Anton Surikov, Aleksandr Voloshin, and Berezovsky, seem, in spite of a grainy photograph, far less credible.41 A senior Chechen field commander, close to Gelaev, says that one of Basaev?s Wahhabi associates tried (unsuccessfully) to convince him to join the incursion, explaining to him that anti-Yeltsin elements in Moscow would remove all obstacles and give Basaev the ?green light;? once he had linked up with the Daghestani Wahhabis and taken Makhachkala, the ensuing crisis would serve to topple Yeltsin, and those who would take power in his place would write off Chechnya and Daghestan, leaving it to the radicals.42 Basaev certainly didn?t trust Berezovsky, but must have thought he could use him to get what he wanted; if this is the case, Berezovsky certainly got the better of the deal. Basaev at least demonstrated, by his behavior during the fall of Groznyi (he marched ahead of troops through a mine field and lost a leg) that he was more than just a buzinesman who sold himself to the Russians, as some strongly believed at the time; but it is well within the realm of the possible that Berezovsky, thanks to the ties he had built up over the years with him, was able to manipulate him. As for the bombings of the Moscow and Volgodonsk apartment buildings, those who believe they were conducted by FSB and GRU elements point first and foremost to the Ryazan incident, during which FSB agents clearly tried to bomb a civilian apartment building; when the plot was foiled and the agents were identified by local MVD and FSB officials, Patrushev initiated a crude and hasty cover up, claiming the whole thing had been a training exercise to test the vigilance of the population.43

Putin?s election, in spite of his skyrocketing popularity, looked anything but guaranteed in the fall of 1999. The Yeltsin camp now faced a powerful and organized opposition, determined to win the forthcoming Duma and presidential elections. The main threat remained Primakov. In the spring, after his dismissal, he had joined a ?party of governors? led by St. Petersburg Governor Vladimir Yakovlev and Tatarstan President Mintimer Shaimiev, Vsya Rossiya (?All Russia?), and formed a political alliance with Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov, who had set up his own vehicle, Otechestvo (?Fatherland?). When the two parties joined forces as Otechestvo-Vsya Rossiya (OVR) for the December 1999 Duma elections, Primakov was named number one on the list. It was clear to everyone that if the bloc did well, as was widely expected, it would serve as a platform to present Primakov for the Presidency, with Luzhkov as his potential prime minister. The threat to the ?Family? was dire; Giorgi Boos, the head of OVR?s campaign staff, even invoked the brutal death of Ceausescu and his wife to state that Yeltsin would meet his end in a ?Romanian scenario.?44 To counter the threat, Berezovsky and his Kremlin allies rapidly set about forming a political movement, the Mezhregionalnoye Dvizheniye Edinstvo (?Interregional Unity Movement?), better known by its acronym Medved (?Bear?) and later renamed Edinstvo (?Unity?) when organized as a party. The movement sought to gather governors who had declined to join OVR (such as Lebed or Primorskiy Krai?s highly corrupt Yevgeny Nazdratenko) under the leadership of the Emergency Situations Minister Sergei Shoïgu, the creator of GUBOP, Alexandr Gurov, and Aleksandr Karelin, a world champion in Greco-Roman wrestling. Its only platform was unconditional support for Putin and it was backed by a hastily set up but massive propaganda apparatus. Berezovsky, desperate to get Putin elected so as to ward off the threat from Primakov, who had promised to destroy his business empire and jail him, also used the media under his control to launch a vicious campaign against both his enemies: Luzhkov, thanks to his notorious refusal to distinguish clearly between public and private funds, made an easy target, whereas Primakov, more subtly, was painted as an aging and ailing Communist dinosaur in the mold of Leonid Brezhnev (Luzhkov on his side relied on Gusinsky?s NTV for violent attacks against Yeltsin and his entourage, but was not as successful as his adversaries). These tactics, combined with a strategic alliance with the Communists, succeeded: OVR, on December 19, barely obtained 13.33 % of the vote, while Edinstvo garnered 23.32%, which, added to the now-pliant Communists? 24.29%, gave the Kremlin broad backing from the Duma for the first time since the end of the USSR. Primakov and Luzhkov immediately understood which way the wind was blowing and promptly switched sides, obediently and shamelessly offering to align OVR with the Kremlin and pledge allegiance to Putin; Primakov, his ambitions crushed, did not even attempt to run in the Presidential election a few months later.

The war in Chechnya was in full swing: Russian artillery and airforce were bombing Groznyi and every other major Chechen town to rubble, provoking a mass exodus of refugees, and the first Federal troops were probing the defenses of the Chechen capital. By this point, the ?Family? had placed all its bets on Putin, fully realizing that they would lose direct control over him once he was elected: they had no other options. Already, Putin was moving to distance himself from Berezovsky; as early as mid-September 1999 the oligarch?s influence on Kremlin policy had visibly declined, though he continued to commit all his assets to Putin?s victory (he also had himself elected Duma deputy for Karachai-Cherkessia, which at least gave him legal immunity; his associate Roman Abramovich did the same, in the region of Chukotka). But the Kremlin remained worried: the presidential election was scheduled for June 2000, and much could happen in the meanwhile; if the campaign in Chechnya bogged down, with high Russian casualties, Putin?s manufactured popularity could plummet as rapidly as it had risen. A decision was thus taken to move up the electoral calendar. On the night of December 31, 1999, Boris Yeltsin appeared on television to announce that he was resigning; this automatically, by law, made his Prime Minister acting President until early elections to be scheduled within three months. Vladimir Putin, on the night of his greatest triumph, conspicuously eschewed the traditional Bolshoi New Year?s Eve Ball, preferring to pop his champagne in the company of his wife and his FSB crony Patrushev in a military helicopter flying over Chechnya. His first Presidential action, just before flying to Mozdok, was to sign a decree granting Boris Yeltsin full immunity from prosecution; on January 3, 2000, he sacked Yeltsin?s daughter Tatyana Dachenko from her position within the Presidential Administration, though he retained other lead ?Family? figures such as Voloshin or his Prime Minister-to-be Mikhail Kasyanov for several years.

Footnotes :

To quote this document :

Post-Soviet Armies Newsletter,

http://www.psan.org/document519.html